First look, then read - Helen Verhoeven at Art Rotterdam

First look, then read. Let your eyes take everything in before forming an opinion and only then read the title. That applies to the viewing of all art, but especially to the newest work by Helen Verhoeven. If you go by the titles alone, you miss the actual subject of the image. It is not the black cat in Black Cat, the white mask in White Mask or the yellow head in Yellow Head; rather, they are a corpse, a pistol—aimed at the viewer—and a machine gun. The subject is violence and its consequences.

The artworks are part of the series Verhoeven has made over the past year titled Because. Because is no more than a prompt toward an explanation, because without further qualification, it has something of a lazy appeal to authority: simply because I say so, simply because it can be done and because I felt like it. Seen this way, it seems to concern senseless violence.

Helen Verhoeven’s work can be seen at the Annet Gelink Gallery stand. At the time of publication, it is not yet clear which work will be shown.

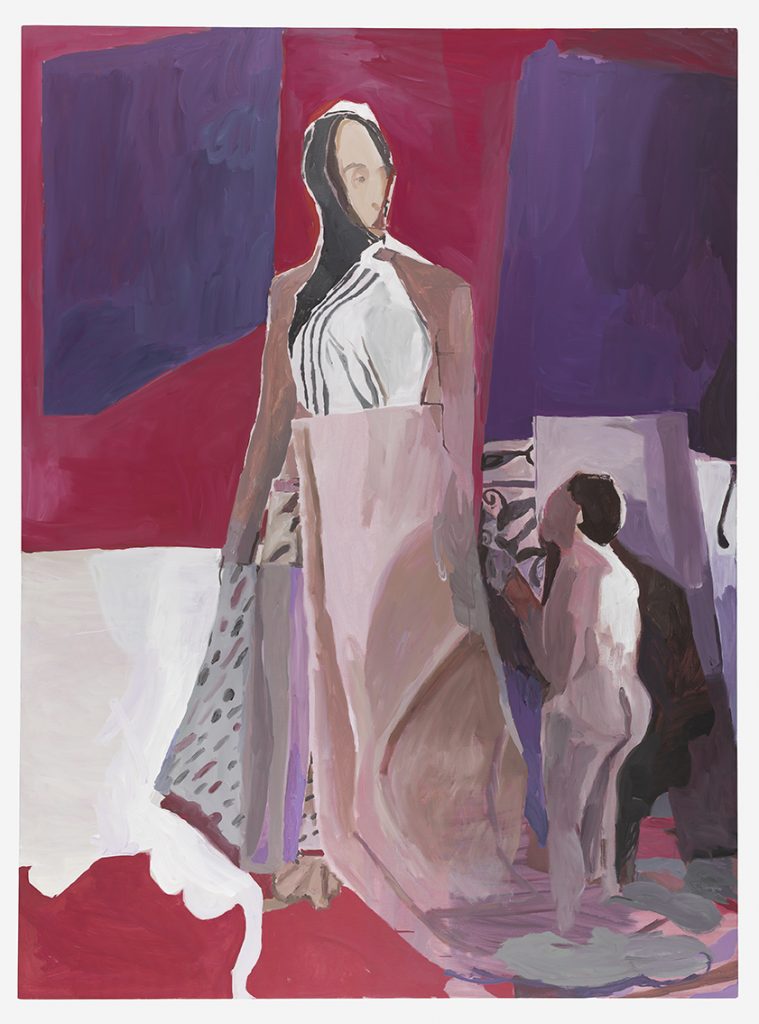

Verhoeven’s work is a combination of figuration and abstraction. She uses different textures and patterns, giving the entirety an almost collage-like effect. In Verhoeven’s work, you can see exactly what is happening on the canvas. You recognise the situations, the spaces, references to current events or historical occurrences and you can interpret the body language and facial expressions of human figures. At the same time, little is worked out in detail, which also gives Verhoeven’s work a magical quality, like a scene from a dream. The image is as tangible as a thought. At any moment, it could burst apart or slip through your fingers.

Verhoeven’s palette also leads you astray. At first glance, the purple, blue and pink feel cheerful, but the colours are almost always accompanied by a grey undertone. This makes them appear matte. The subjects, by contrast, are generally darker and anything but naive. Thematically, Verhoeven connects autobiographical elements with universal themes such as fertility and beauty, also touching on subjects like power relations and death. The work in Because is no exception.

“My paintings often depict unpleasant things, but hopefully, with a certain lightness, because humour is ultimately the best antidote to all misery,” she said a few years ago to Het Parool. Because of that lightness, Verhoeven’s work always presents you with a whole range of emotions. In Black Cat, we see a black cat next to what appears to be a deceased person. The black cat sheds a tear, but in such a way that it feels light. Something cheerful.

Helen Verhoeven (Leiden, 1974) lives and works in Berlin. She has a studio in Lichtenberg, a district in former East Berlin, just outside the S-Bahn ring. Her studio is housed in an old Stasi listening station and overlooks a former Stasi prison. At first, she did not know what had taken place there. That might even have been too much for someone who, for a time, actively sought out difficult emotional and mental experiences and drew on them for her work.

One of the places where she encountered such intense experiences was the secondary school Verhoeven attended in 1986. That year, the Verhoeven family moved from the neatly groomed town of Oegstgeest to the metropolis of Los Angeles due to her father’s film career. A great contrast in terms of liveliness, but also in terms of society. On the surface, it resembles ours, but one that overlooks the enormous differences in opportunity, health and prosperity.

Verhoeven’s parents moved to L.A. with a progressive, European mindset. As a result, they chose to send Verhoeven and her sister to a local public school, as was customary in the Netherlands. At that school, she came into contact with aggression, alcohol, drugs, sexual boundary-crossing behaviour and gangs. “I arrived as a child who had experienced nothing and within a year, I felt as though I had experienced just about everything and the innocence of my youth was gone.” From the age of 15, she attended another school that was geographically close by, but with a completely different composition.

During her American academy years at the San Francisco Art Institute and New York Academy of Art, she actively sought out intense emotional experiences—shocks she could process in her work. “I wanted to see, feel and experience the bad; as if only that were real life.” For example, she worked at an abortion clinic in a disadvantaged neighbourhood, where she encountered the most heartbreaking situations. Verhoeven comments, “A very young girl came in for an abortion. She had an enormous, homemade tattoo of a penis on her stomach. Terrifying—that image has always stayed with me.”

She also worked for a while in an emergency room, dissected corpses in a laboratory and helped out for some time at a homeless shelter. Verhoeven continues, “I collected an endless well of feelings alongside factual knowledge.” She justified this to herself by making work about it, but this has come at a price: “It produced interesting art—and still does—but I also suffered from those deliberately sustained traumas.”

During her working process, Verhoeven seals off her studio hermetically from the critical gaze of outsiders. A single word about a work that is not yet finished can ruin a painting. Verhoeven explains, “I find making art extremely private, very personal.” For a while, she made a lot of work about mothers and children as a way of dealing with the fact that she was unable to become pregnant. A month later, she turned out to be expecting after all. Verhoeven says, “I find painting to be a kind of exorcism anyway. You let it go, you let it out and you move on.”

That not every work needs to be preceded by an intense emotional experience is demonstrated by the work Verhoeven has made on commission. In 2015, she completed an ambitious work for the Supreme Court of the Netherlands and in 2021, The Family, an imposing group portrait of the Royal Family, starting with Juliana of Stolberg. Both works of art were preceded by extensive studies.

The Supreme Court painting is imposing in every respect. The canvas measures no less than 4 by 6.5 meters—Verhoeven worked on it for a year—and is packed with historical and art-historical references to the development of Dutch law. But here, too, all is not peace and harmony. The Supreme Court rather holds up a mirror to us. The judiciary and rule of law as we know them are just as fragile as the dream images in a series like Because. Over the centuries, a price has been paid for them and if we do not maintain them, they will disappear like snow in the sun.

On the walls of the courtroom, we see former politicians, scholars, heads of state and philosophers. Most striking is the famous painting of the lynched De Witt brothers by Jan de Baen. In front of it sits the Supreme Court under the leadership of its president, Lodewijk Ernst Visser, who was the first Jewish-Dutch president of the Supreme Court, but was dismissed by the German occupiers in 1941—without public protest from the other justices. In the foreground, we see a crowd of sad, angry, lonely, kind and familiar figures who together form our society.

Helen Verhoeven’s work is included in, among others, the collections of the Centraal Museum, Stedelijk Museum and Bonnefantenmuseum, where she held a solo exhibition in 2018. Her work can also be found in the collections of the Saatchi Gallery, Museum of Contemporary Art in Miami, DSM, De Nederlandsche Bank, Eneco and Rabobank. In 2008, she won the Royal Award for Modern Painting, followed by the Wolvecamp Prize in 2010 and ABN AMRO Art Award in 2018. Helen Verhoeven is represented by the Annet Gelink Gallery.

Written by Wouter van den Eijkel