Painting Through Violence: A Conversation With Diana Al-Halabi

The work of Diana Al-Halabi (1990, Lebanon) is deeply personal and political. She speaks about hunger, war, and dehumanisation with clarity and urgency, her voice unwavering. Her latest works at Art Rotterdam Prospects, Clean Cut (2024) and Blow Up (2025), confront themes of power, oppression, and the ways in which violence is sanitised and dismissed.

Throughout the interview, a small, fluffy green parakeet called Bubu flutters around her, chirping, pressing tiny, tender kisses to her lips - bringing a fleeting lightness to the conversation.

What is the common thread in your work?

“My practice is interdisciplinary; I can’t call myself only a filmmaker or only a painter,” Diana explains. The medium she chooses is always dictated by the urgency of the subject matter. “If I’m speaking about something that is happening right now, I have to respond differently than when I’m dealing with something from the past.”

Diana’s work critically examines power structures rooted in verticality; systems where power is imposed from above. “I work against anything that comes top-down. That means oppressed versus oppressor, colonised versus coloniser,” she says. This tension is central to her practice, where she usually moves from the deeply personal to the larger political framework in which these dynamics play out.

But in her film The Battle of Empty Stomachs, the process was reversed. “I had been researching this project since 2021, trying to juxtapose two types of political hunger,” she explains. “Famine is a top-down mechanism, it comes from the government, imposed on the people. Hunger strikes, on the other hand, move in the opposite direction, from the individual prisoner up, as an act of resistance.”

But as she worked on the film, reality caught up with her. “I asked myself, what do I actually know about hunger? Nothing, right? The biggest thing I knew was fasting. That’s it.” Then, starvation in Gaza escalated. “Witnessing a genocide with political starvation while making a film about hunger was overwhelming. It was happening in real time.”

The grant by Mondrian Fund supported the creation of that film, right?

“Yes, The Battle of Empty Stomachs was supported by both Mondrian Fund and the IFFR RTM Pitch Award. The award money was strictly for production costs, so Mondrian Fund personally helped me during the creation process,” Diana notes.

Her research spanned two years, while the film itself took about six to seven months to make. But after its completion, she found herself needing to shift mediums. “I write everything in my films, even the poetic texts. But at some point, language started to feel too constrained. Words were too small, too narrow for what I was witnessing.”

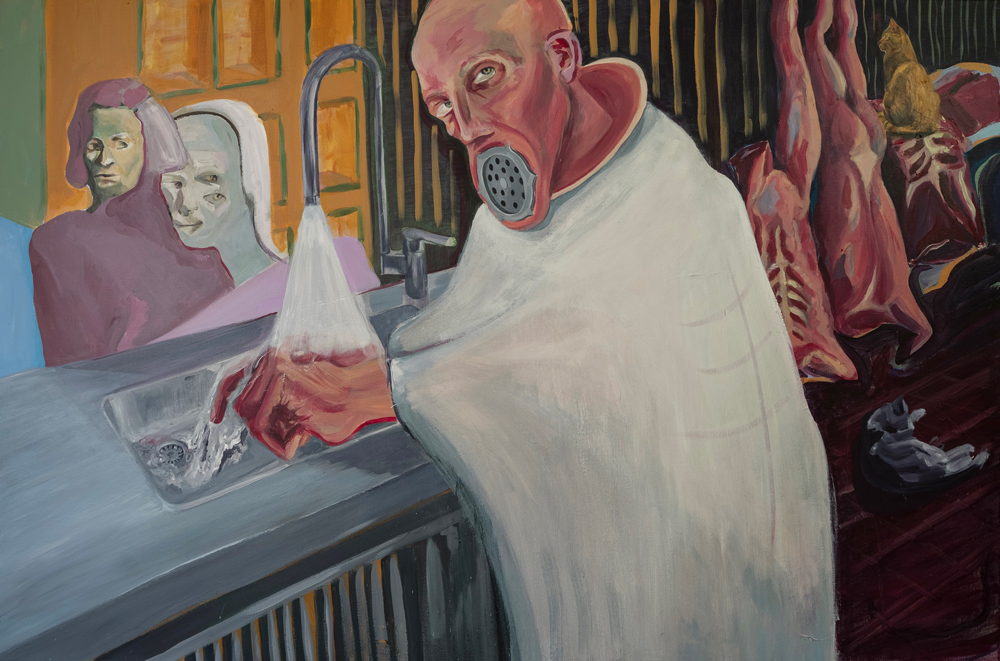

This return to painting resulted in Clean Cut, 2024, a work that she will show at Art Rotterdam Prospects.

What influenced the creation of Clean Cut?

“As I was reading Bertolt Brecht’s 1935 essay Writing the Truth, Five Difficulties, there was a passage that captivated me about people wanting to critique fascism but not capitalism,” Diana says. “Brecht compares it to wanting to eat veal without seeing the calf being butchered, and being satisfied as long as the butcher washes his hands. That struck me deeply.”

This idea is at the core of Clean Cut, 2024. In the painting, a butcher is depicted washing his hands, while a meat grinder emerges from his mouth. Two women look on with suspicion. “Having lived in the West for five years, I experience these double standards firsthand. People scrutinize others with suspicion, yet there’s an implicit hierarchy in who is allowed to critique violence. When someone says, ‘Oh no, those poor Israelis,’ they refuse to acknowledge the root of the problem and that’s exactly what Brecht wrote back then. People are willing to critique fascism, but not capitalism. The same pattern repeats today: they condemn violence but won’t critique Zionism. Or they denounce Nazi fascism but refuse to question Zionism. It’s guilt-washing, just like the butcher washing his hands of the blood.”

The title Clean Cut references how modern warfare sanitizes violence. “Israel bombs Gaza in a ‘clean’ way. It’s vertical violence - detached, almost invisible. A missile drops from the sky and erases the act of killing. But a knife moves horizontally, close and direct. One is considered clean, the other dirty”.

The bodies in the painting are not animals; they are humans. “This is also a direct response to Zionist rhetoric that calls Palestinians and Lebanese ‘human animals.’ But historically, Jewish victims of the Holocaust were called the same by Nazis. It’s a cycle of dehumanisation.”

Why does the medium of painting resonate so strongly with your work right now?

“I think no medium can amount to the disastrous reality,” she says, reflecting on the overwhelming violence and suffering that images of the war in Gaza attempt to capture. Yet, what troubles her just as much is how quickly these images vanish. “Nowadays, images disappear so fast, lost in the abyss of the internet. I think we must not allow scroll amnesia to erase the vastness of what we have witnessed. Before the internet, images documenting war remained in people's eyes. Look at the Vietnam War, some images remain iconic for the resistance and suffering they hold.”

Painting is a way to hold onto images that have unsettled her. “I saw a picture of a pile of brutally butchered Palestinian bodies, with cats sitting on top of them and I kept wondering: Are the cats starving and looking for food? Are they grieving? Or are they warming up the bodies because they feel the coldness of their deaths?”

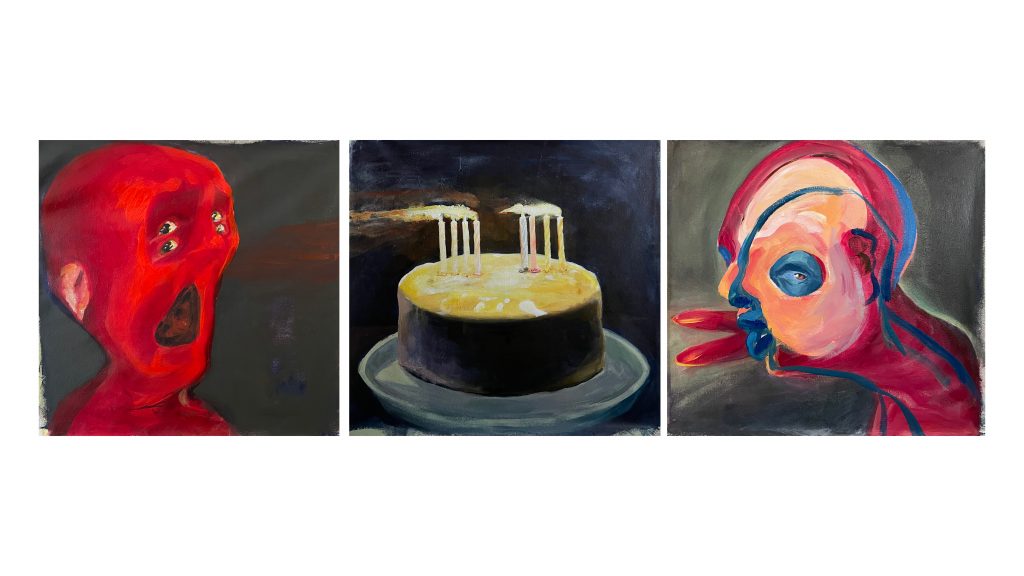

She also recalls seeing photos of children and celebrities writing messages on missiles, missiles that would later be dropped on Palestinians. They directly influenced Blow Up, the triptych she is currently painting and will be revealed at Art Rotterdam Prospects. “This act of genocide is framed as something patriotic, but it’s a form of brainwashing, indoctrinating people into horrific violence when they don’t even understand what they are part of.”

The weight of such imagery demands permanence. She turns to painting precisely because it resists this cycle. “I felt the ethical responsibility not to reproduce those images but to at least find a way to talk about them through art. Painting is about ensuring that such moments are not just a scroll, but they are here to stay - because forgetting is too easy, and denial even easier.”

With firm persistence, Bubu breaks through the heaviness of the conversation, pressing soft kisses to Diana’s lips - as if trying to comfort her. She kisses him back and whispers softly, “Habibi Bubu, I love you too.”

It’s an interruption so absurd that Bertolt Brecht himself might have written it, a moment of tenderness breaking through the weight of war, pulling us, if only for an instant, out of the frame.

Written by Emily Van Driessen