Coming soon

Coming soon

Select type

For the ninth consecutive year, the NN Art Award will be presented in 2025 to a promising artist showcasing their work at Art Rotterdam. This year’s nominees are Diana Scherer (andriesse eyck galerie), Marcos Kueh (Prospects section of the Mondriaan Fund, courtesy of Galerie Ron Mandos), Pris Roos (Mini Galerie) and Bodil Ouédraogo (Prospects section of the Mondriaan Fund). The work of the four nominees will be on view at Kunsthal Rotterdam from 15 March until 11 May 2025.

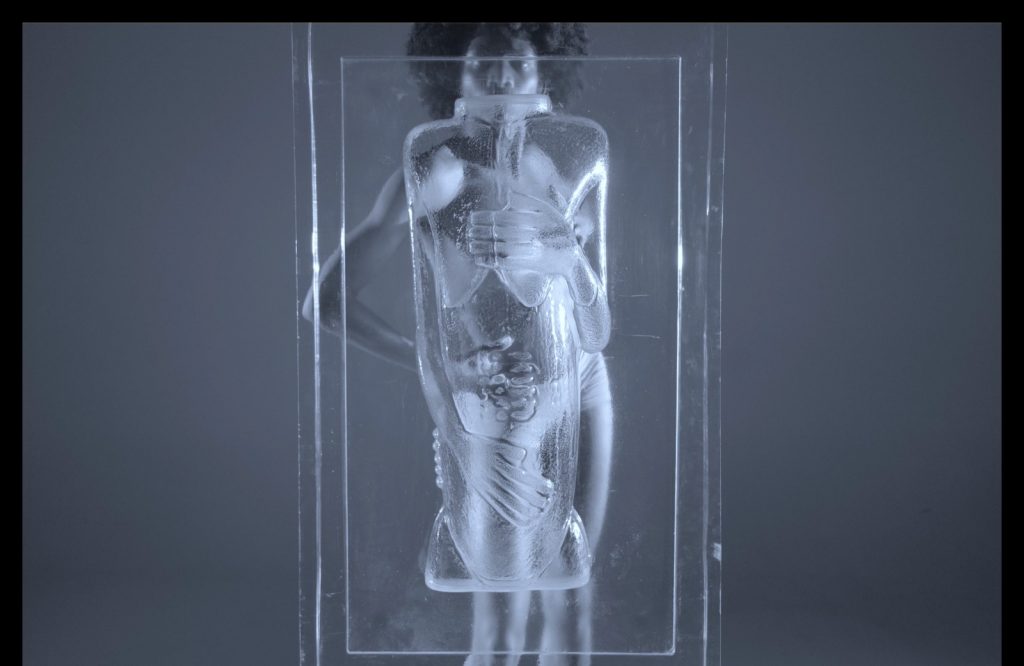

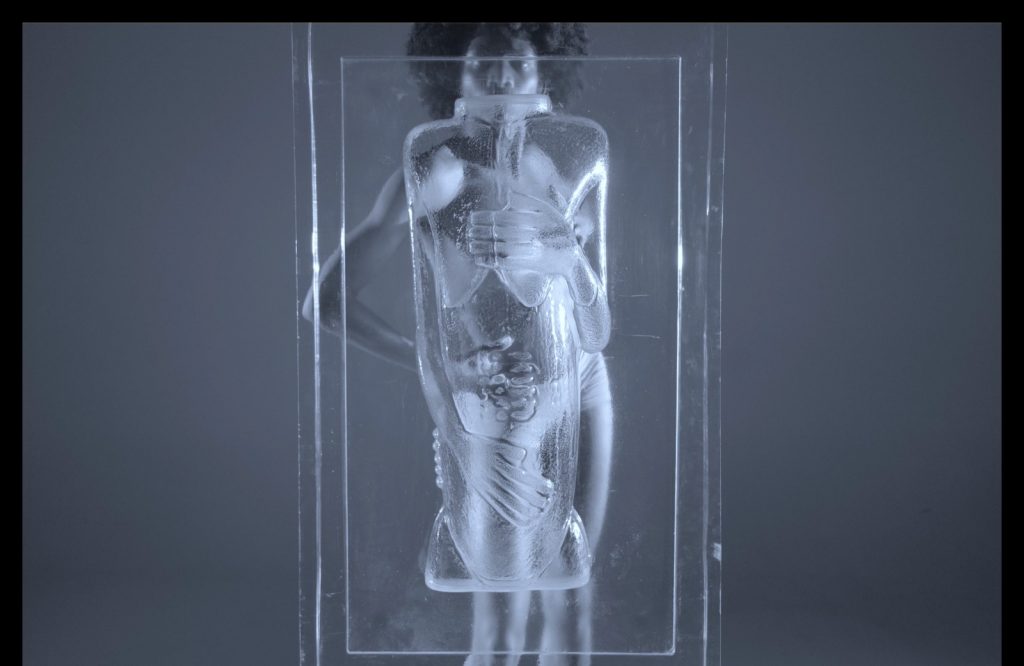

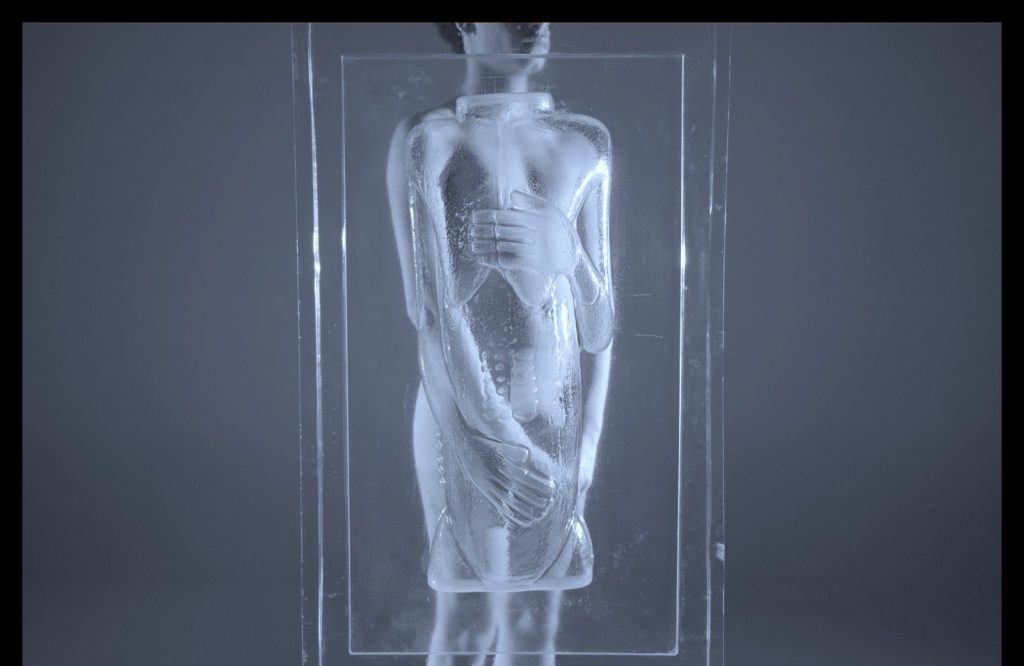

Bodil Ouédraogo (1995) is an interdisciplinary visual artist with a focus on the art of dressing up. Her layered work explores how we assign value and status to objects or people. She examines different ‘cultural tools’ that assign value or legitimacy to objects or people such as framing, preserving, distancing. She tries to dissect these tools, and reuse them to create movement in how we experience fixed ideas about people or objects. For Ouédraogo, the art of dressing up is far more than just clothing — it is a cultural context, a language that intertwines historical and social meanings. Drawing from her bicultural background, with roots in both the Netherlands and Burkina Faso, she weaves together materials, techniques and cultural references from West Africa and Europe into sculptural objects and installation created not only to be seen but also to be experienced. She approaches her practice in distinct artistic chapters, each investigating different aspects, while often combining cultural elements that may initially seem worlds apart.

A recurring thread in her work is the way we present ourselves in spaces, with clothing serving as an archive of heritage and identity. Ouédraogo seeks ways to honour all parts of the self, with a particular interest in those who came before us. Her installations and performances — where textiles, dance, photography, video, sound and sculpture come together — give rise to new narratives. They become innovative, hybrid forms, in which fashion operates as a conceptual and critical medium.

Ouédraogo does not view identity as a collection of isolated elements, but rather as a network of interconnected stories that form a whole, effectively seeking connections. Through her work, she seeks to render this complexity visible, while rediscovering aspects of identity that have been forgotten or overlooked. She examines the interplay between various cultural aspects within Black culture and the European Afro-diaspora. Her multidisciplinary practice generates a rich, layered materiality in which the art of dressing up comes to life. Moreover, when her work becomes part of a shared reality, it creates a collective experience.

In her latest research she is fascinated by traditional West-African sculptures and ways of posing, bearing and positioning the self. Many of these artworks were taken to Europe as looted art and contain details that inspire her. At Art Rotterdam, Ouédraogo will present 3D-printed sculptures in PLA (a biodegradable plastic), cast aluminium and coloured glass, in collaboration with professional studios such as Audrey Large, Studio Lemarez, and Van Tetterode Glass Studio. These objects explore the relationships between bodies and show how materiality can contribute to a new meaningful connections with who went before us. For these pieces, Ouédraogo translates West African traditional wooden sculptures from the private collection of her father Mamadou Ouédraogo into a contemporary context, where she delves deeper into the boundary between human and sculpture.

Movement plays a crucial role in her installations. During Amsterdam Fashion Week and at the Stedelijk Museum, she presented performances in which dancers wore semi transparent grand-boubou, a three piece suit onto which projections were staged. Here, the body acts as a living archive, engaging in dialogue with fabric, movement and form. Fashion thus becomes a dynamic medium, continually taking on new meanings.

Ouédraogo’s practice is rooted in intensive research into the history of the self, and ways of self presenting. She is informed by research about the art of dressing up in the Afro diaspora as well as in West Africa, where she combines family visits with research on the art of dressing up in Burkina Faso, as well as in Mali, Ghana and Nigeria. She translates this knowledge into a visual language that is both deeply personal and universally resonant.

At Art Rotterdam, her work will be on view in the 13th edition of Prospects, an initiative by the Mondriaan Fund. This exhibition presents work by 116 artists who received financial support in 2023 to aid them in the start of their careers. The section is curated by Johan Gustavsson and Louise Bjeldbak Henriksen. Explore all Prospects artists here.

Can you tell us more about the work you are presenting at Art Rotterdam and Kunsthal?

In my work, I aim to find connections in different cultural ways of ‘self presenting’. I examine different ‘cultural tools’ that assign value or legitimacy to objects or people. I try to dissect these tools, and reuse them to create movement in how we experience fixed ideas about people or objects. I try to shuffle the environment by presenting an alternative that allows another perspective. I try to show an alternative hierarchy than the one usually presented. I’m doing this by combining styles that uplift and question each other. Together they give me a broader, more grounded vision on how to be rooted.

For the works that I’ll show at Kunsthal and Art Rotterdam, I do that by embodying African wooden art from the personal collection of my father, Mamadou Ouédraogo. In these pieces, parts of our heritage, you see how the people who went before us used to present bodiesthroughsculptures. What can I learn from the way these bodies pose? How can we stand in line with those who went before us? How do you visualise an imagination where all these parts are layered and transparent? I think that trying to portray all these parts of the self and giving light to forgotten or neglected parts of the self, asks for radical imagination. It’s a matter of taking up space, by presenting an alternative where you show that you are overly connected.

My work is an exploration of posing, bearing and positioning yourself. A longing for those who lived before us. Longing to express togetherness through material heirlooms. I try to capture the human intimacy of West African traditional sculptural wooden art. Expressing the generational connection by enlarging different intimate poses to human size. I propose to give them space in the present.

What are your plans for 2025?

I would like to delve deeper into the boundary between human and sculpture, how can I bestow these sculptures with an equal sense of dignity? I look forward to developing new techniques and challenging myself in the workshop. My aim is to create a visual experience where I can portray an alternative reality. To create something that cannot be placed in a particular category. An unfamiliar, science fiction reality. In October, my work will be shown in a solo exhibition at Melkweg Expo in Amsterdam.

How did you feel when you heard you were nominated for the NN Art Award?

It is special to experience that people see what you do and believe in it. I feel blessed to be able to achieve this trust. I would like to thank the NN Art Award for the special opportunity. The fact that we will also exhibit our work in Kunsthal Rotterdam is wonderful.

If you won the award, what project would you pursue immediately?

I would love to explore and develop glass and aluminum casting techniques, as these are valuable materials. Winning would grant me the freedom to fully develop my ideas.

Bodil Ouédraogo studied Fashion at ArtEZ and the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, where she still lives and works. In 2019, she won the Dutch Design Award in the Young Designer category, and in 2022, she received the Amsterdam Prize for the Arts. Her work “My Hair, a Border” is part of the collection of the Stedelijk Museum, where it is currently on view in the permanent collection display ‘NOW – 1980’. Her work has also been presented at the Gwangju Biennale 2024, Dutch Design Week, the TextielMuseum, Het Nieuwe Instituut and Framer Framed. Additionally, Ouédraogo designed a collection for fashion house Patta. In 2023, she was named one of the fifty FD Talents of the Year by Het Financieele Dagblad.

The winner of the NN Art Award 2025 will be announced on Friday 28 March at 20:00 in Kunsthal Rotterdam. During this celebratory evening, all exhibitions, including the NN Art Award exhibition, will be freely accessible to attending guests.

Geschreven door Flor Linckens

Ivan Gallery from Bucharest will present the work of Shahin Sharafaldin at Art Rotterdam (28-30 March 2025). His work will be shown in the New Art Section, which was curated by Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu. In his paintings, Sharafaldin explores representations of masculinity and queer identity, deliberately challenging overly homogeneous and simplistic depictions. His figurative practice navigates the space between intimacy and monumentality, with a focus on the physical and the imaginary.

Sharafaldin’s sensitive and layered work delves into themes of friendship, homosexuality, connection, desire and utopian ideals, while also offering a critical reflection on the ways in which identity is shaped and perceived. His approach to queerness is distinctly intersectional: he is fascinated by its nuances, depth and complexity, viewing it through the lens of class, race, gender and nationality. This perspective also compels him to examine broader societal structures, such as heteronormativity and patriarchal power dynamics.

Sharafaldin’s vivid oil paintings are composed with a carefully calibrated palette, creating a sensuous tension that balances strength and vulnerability. His figurative canvases depict both idealised and everyday scenes: a dreamlike figure reclining on a rock, an unguarded moment in a bedroom, or an explicitly erotic encounter between two bodies.

The setting often plays a crucial role in his work. Sharafaldin deliberately pushes the boundaries between private and public spheres, sometimes allowing the background to take centre stage. In some paintings, the viewer is offered a still, intimate glimpse into shadow-filled rooms. Melancholic, sometimes even oppressive interiors, where absence becomes a palpable presence. Tattered curtains rippling in soft light, beds that seem to carry the weight of memory — these are recurring motifs in his paintings.

Sharafaldin also portrays homosexual bodies that simply exist. In “Heatwave” (2023), a work that will be exhibited at Art Rotterdam, he presents a nude figure that isn’t posing for the gaze of another but is just existing in a moment of repose — a subtle yet resonant expression of queer representation. The composition shows a nude male figure reclining in a lounge chair, immersed in complete relaxation. The scene exudes an air of nonchalance and self-contentment, with the figure entirely turned inward. The way Sharafaldin renders the body — hairy, at ease, in an unselfconscious pose — stands in stark contrast to traditional representations of masculinity in art history. This is not a heroic or idealised nude but rather a candid moment of contemporary life.

Sharafaldin’s painterly technique accentuates the interplay between realism and expressivity. Loose, visible brushstrokes add texture to skin and fabric, while the contours of the body are rendered with meticulous precision. The surrounding green tones in the background and upholstery envelop the figure, creating a sense of unity with the space. The smartphone in his hands and the headphones on his head anchor the work firmly in the present, reinforcing a sense of introspection and isolation.

At times, Sharafaldin’s work evokes echoes of classical painting traditions — baroque chiaroscuro, symbolist undertones, a vitalist energy — while simultaneously integrating contemporary queer perspectives. Through this layered approach, he challenges both the conventions of art history and the norms of queer representation.

Shahin Sharafaldin was born in Vancouver in 1995. He lived in Montreal until recently: he relocated to London last summer. He studied Fine Arts and Curatorial Practice at Emily Carr University of Art + Design in Vancouver and in 2016, he spent a period at the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam. His work has been exhibited in Canada and the United States, and in 2021 he completed a residency at Céline Bureau in Montreal. With his participation in Art Rotterdam, he makes his debut in the Netherlands, placing his work within a broader European context.

Shahin Sharafaldin’s work will be presented by Ivan Gallery in the New Art Section at Art Rotterdam.

Written by Flor Linckens

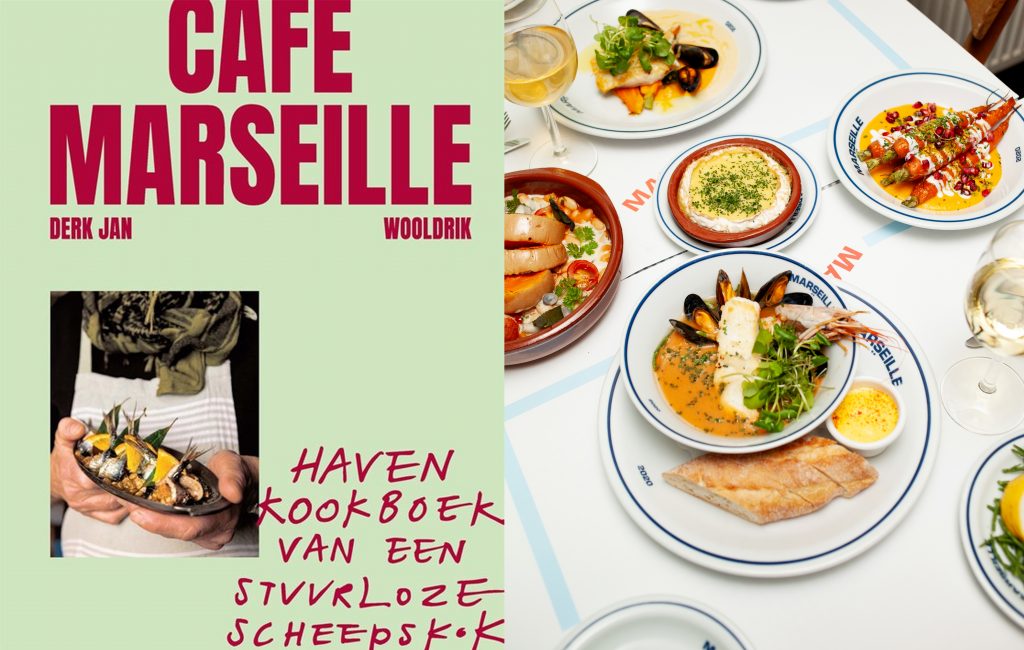

For the first time at Rotterdam Ahoy, Art Rotterdam promises to make a big impact in terms of catering. Experience the charm of the South of France at the fair with the Pop-up restaurant & apéro bar Café Marseille!

Chef Derk Jan Wooldrik and Kristian de Leeuw bring the refined flavors of the Mediterranean to the fair in a stylish setting with delicious dishes such as homemade fish soup, chickpea panisse, and bouillabaisse. Whether for a full lunch or dinner at long tables, or for quick small dishes like fritto misto, Zeeland oysters, and shrimp croquettes, there is always something special to enjoy, served with (natural) wines and their own beers.

Opening hours Pop-up restaurant and apéro bar:

Thursday March 27 (Opening, invitees only): 11.00 – 21.00 hrs

Friday 28 to Sunday 30 March: 11.00 – 19.00 hrs

Booking in advance is not necessary, but make sure you are there on time, you don’t want to miss this!

Also available for purchase at the pop-up restaurant: Het havenkookboek van een stuurloze scheepskok (in Dutch).

This is not your typical cookbook. It is the journey Wooldrik made through eight port cities, a record of his cooking adventures as a ship’s cook, where he constantly lost – and then found – himself in a maze of ingredients, smells, and memories.

Through his work, artist Janne Schimmel (b. 1993, The Netherlands) bridges the digital and physical worlds, exploring gaming and technology from a fresh perspective. This year, he is presenting Between Modder and Mud (2024) in the Prospects section of Art Rotterdam, a gaming sculpture featuring a self-designed game that invites interaction and reflection.

What is the common thread in your work?

“Gaming has always played a role in my work,” Janne explains. “What fascinates me is the contrast between how game worlds are designed and how gamers shape their physical spaces. Take World of Warcraft, for example: a richly detailed, magical world filled with crystals and spiritual elements. Yet, the typical gamer’s room is often minimalist and sleek, with LED lighting, streamlined furniture, and cold, industrial consoles. These two worlds are in stark contrast, and in my work, I aim to bring them together.”

His sculptures expose this tension and challenge the conventional design of gaming hardware. “The devices we rely on to connect with the digital world are often designed to convey power and speed, while softer, more emotional qualities are rarely considered. I want to change that narrative.”

Why is gaming hardware and design often so limited aesthetically?

“I think it stems from our performance culture,” says Janne. “In the 1990s, during LAN parties—gatherings for computer enthusiasts—gamers would come together to showcase the fastest and most powerful computers. They would open the side panels of their cases to proudly display the hardware inside. This led to an aesthetic centred around components that exude strength and speed.”

In his sculptures, he literally exposes these components—motherboards, processors, and graphics cards—but contrasts them with materials such as crystals, jewellery, and stones. “By placing these opposing elements side by side, I want to highlight how narrow the aesthetics of gaming hardware have become and create space for something softer, something less rational.”

He also sees the influence of patriarchal structures in this. “The idea that hardware must be powerful and masculine leaves little room for emotions and softer aesthetics. A lot of these traditional ideas are still deeply ingrained.

Gaming is often seen as a solitary activity, but in your work, you highlight the power of gaming communities and user-generated content. Can you elaborate?

“Gaming is much more than an individual experience,” Janne emphasises. “The strength of communities lies in the sharing of knowledge and creativity. A great example is the modding community, where gamers modify existing games. This started in 1993 when the developers of Doom made their code public, allowing players to make their own modifications. That moment changed the industry forever.”

Janne also speaks highly of the homebrew community, where people create entirely new games for old consoles like the Game Boy or Nintendo DS. “What I find so inspiring about this is how the community reactivates outdated technology and challenges the commercial gaming industry. But perhaps even more importantly, they create space for their own stories. The mainstream gaming industry is still dominated by white men, who tend to tell a very singular type of narrative. Homebrew creators break through that. In doing so, they rewrite and repair the stories that are being told.”

These communities are a direct source of inspiration for Janne. He also incorporates their shared techniques and code into his own games. On his sculptural consoles, visitors can not only play his self-made games but also games created by others in these communities, such as LesbiAnts, Toni Catino, a game about lesbian ants. “Just the title alone is genius,” he laughs. “It’s the perfect example of a story that would never emerge from the mainstream industry. These kinds of games show why these communities are so important.”

How has the Mondriaan Fonds grant influenced your work?

“The grant gave me the freedom to explore my creative processes in greater depth,” says Janne. A significant part of the funding was used to invest in a CNC machine, which allows him to cut digital designs with organic shapes into wood and other robust materials with extreme precision. But what fascinates him most is that the process does not end with the physical form.

“I first turn my digital designs into physical 3D objects. Then, I scan those objects back into a digital model and share them with the community. They can integrate these models into their own designs or 3D print them, bringing them back into the physical world. This creates a continuous exchange between the digital and the physical.”

This principle of reuse is also reflected in his design pieces. “One of my sculptures started with an IKEA chair I’ve had since I was 11 years old. When the armrest broke, I repaired it by casting a new one in aluminium. That repair later inspired the sculptural forms of my design chairs and benches.”

What will you be showing at Art Rotterdam?

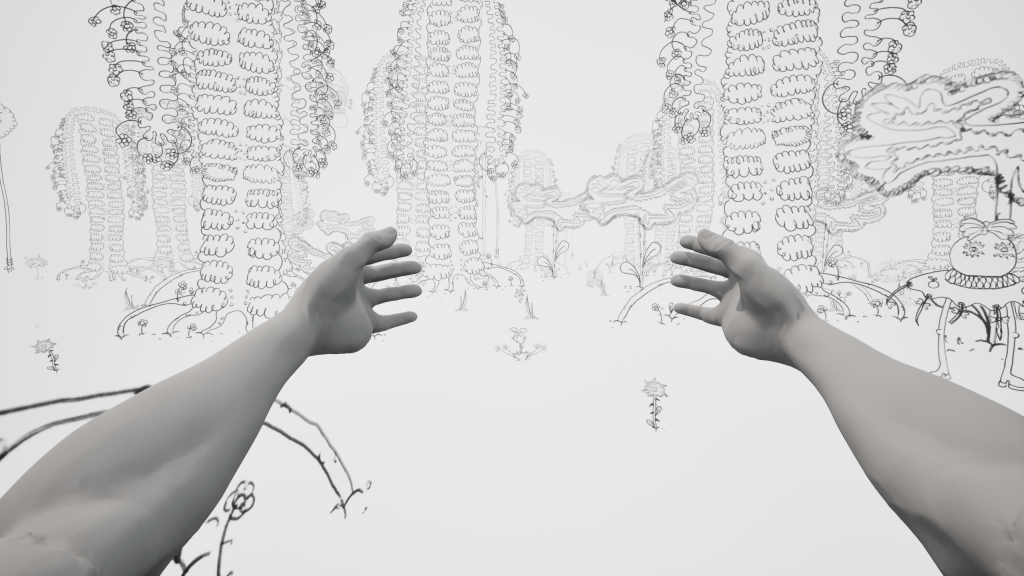

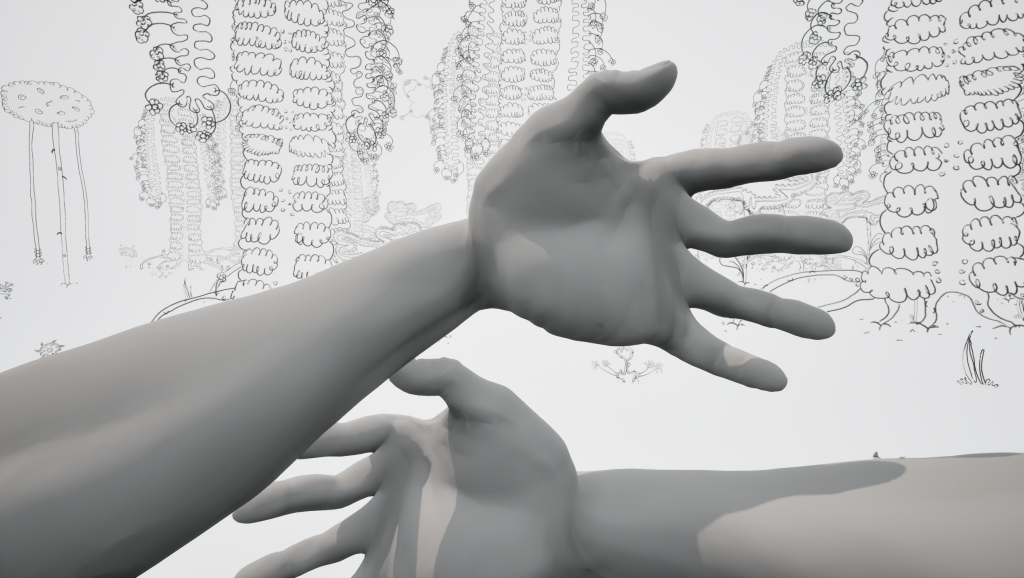

At the Prospects section of Art Rotterdam, Janne is presenting Between Modder and Mud (2024), a gaming sculpture where visitors can play his self-developed game First Person Hugger (2024).

“I wanted to create a game where compassion takes centre stage. In many commercial games, violence is a central element, and I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing,” Janne says. “I grew up with it too, but if I were to create the same thing now, it wouldn’t add anything new. In First Person Hugger, you don’t see the world through the barrel of a gun, as in a traditional first-person shooter, but through open arms. Instead of shooting, the player’s main interactions are hugging and talking.”

This idea was sparked by a moment that has always stayed with him. “I was gaming as a teenager when my mother walked in. She saw a bouquet of flowers in the game and said, ‘Give those flowers to a woman.’ But the only thing I could do was use them as a weapon. That made me realise how limited in-game interactions often are. I want to create something that offers a completely different perspective.”

Written by Emily Van Driessen

The work of Diana Al-Halabi (1990, Lebanon) is deeply personal and political. She speaks about hunger, war, and dehumanisation with clarity and urgency, her voice unwavering. Her latest works at Art Rotterdam Prospects, Clean Cut (2024) and Blow Up (2025), confront themes of power, oppression, and the ways in which violence is sanitised and dismissed.

Throughout the interview, a small, fluffy green parakeet called Bubu flutters around her, chirping, pressing tiny, tender kisses to her lips – bringing a fleeting lightness to the conversation.

What is the common thread in your work?

“My practice is interdisciplinary; I can’t call myself only a filmmaker or only a painter,” Diana explains. The medium she chooses is always dictated by the urgency of the subject matter. “If I’m speaking about something that is happening right now, I have to respond differently than when I’m dealing with something from the past.”

Diana’s work critically examines power structures rooted in verticality; systems where power is imposed from above. “I work against anything that comes top-down. That means oppressed versus oppressor, colonised versus coloniser,” she says. This tension is central to her practice, where she usually moves from the deeply personal to the larger political framework in which these dynamics play out.

But in her film The Battle of Empty Stomachs, the process was reversed. “I had been researching this project since 2021, trying to juxtapose two types of political hunger,” she explains. “Famine is a top-down mechanism, it comes from the government, imposed on the people. Hunger strikes, on the other hand, move in the opposite direction, from the individual prisoner up, as an act of resistance.”

But as she worked on the film, reality caught up with her. “I asked myself, what do I actually know about hunger? Nothing, right? The biggest thing I knew was fasting. That’s it.” Then, starvation in Gaza escalated. “Witnessing a genocide with political starvation while making a film about hunger was overwhelming. It was happening in real time.”

The grant by Mondrian Fund supported the creation of that film, right?

“Yes, The Battle of Empty Stomachs was supported by both Mondrian Fund and the IFFR RTM Pitch Award. The award money was strictly for production costs, so Mondrian Fund personally helped me during the creation process,” Diana notes.

Her research spanned two years, while the film itself took about six to seven months to make. But after its completion, she found herself needing to shift mediums. “I write everything in my films, even the poetic texts. But at some point, language started to feel too constrained. Words were too small, too narrow for what I was witnessing.”

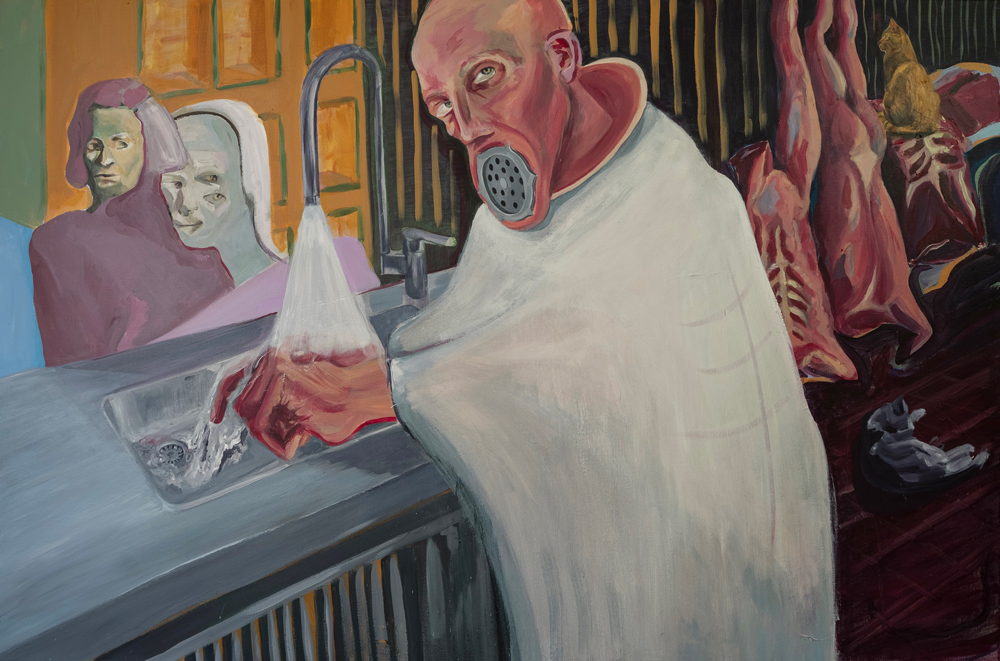

This return to painting resulted in Clean Cut, 2024, a work that she will show at Art Rotterdam Prospects.

What influenced the creation of Clean Cut?

“As I was reading Bertolt Brecht’s 1935 essay Writing the Truth, Five Difficulties, there was a passage that captivated me about people wanting to critique fascism but not capitalism,” Diana says. “Brecht compares it to wanting to eat veal without seeing the calf being butchered, and being satisfied as long as the butcher washes his hands. That struck me deeply.”

This idea is at the core of Clean Cut, 2024. In the painting, a butcher is depicted washing his hands, while a meat grinder emerges from his mouth. Two women look on with suspicion. “Having lived in the West for five years, I experience these double standards firsthand. People scrutinize others with suspicion, yet there’s an implicit hierarchy in who is allowed to critique violence. When someone says, ‘Oh no, those poor Israelis,’ they refuse to acknowledge the root of the problem and that’s exactly what Brecht wrote back then. People are willing to critique fascism, but not capitalism. The same pattern repeats today: they condemn violence but won’t critique Zionism. Or they denounce Nazi fascism but refuse to question Zionism. It’s guilt-washing, just like the butcher washing his hands of the blood.”

The title Clean Cut references how modern warfare sanitizes violence. “Israel bombs Gaza in a ‘clean’ way. It’s vertical violence – detached, almost invisible. A missile drops from the sky and erases the act of killing. But a knife moves horizontally, close and direct. One is considered clean, the other dirty”.

The bodies in the painting are not animals; they are humans. “This is also a direct response to Zionist rhetoric that calls Palestinians and Lebanese ‘human animals.’ But historically, Jewish victims of the Holocaust were called the same by Nazis. It’s a cycle of dehumanisation.”

Why does the medium of painting resonate so strongly with your work right now?

“I think no medium can amount to the disastrous reality,” she says, reflecting on the overwhelming violence and suffering that images of the war in Gaza attempt to capture. Yet, what troubles her just as much is how quickly these images vanish. “Nowadays, images disappear so fast, lost in the abyss of the internet. I think we must not allow scroll amnesia to erase the vastness of what we have witnessed. Before the internet, images documenting war remained in people’s eyes. Look at the Vietnam War, some images remain iconic for the resistance and suffering they hold.”

Painting is a way to hold onto images that have unsettled her. “I saw a picture of a pile of brutally butchered Palestinian bodies, with cats sitting on top of them and I kept wondering: Are the cats starving and looking for food? Are they grieving? Or are they warming up the bodies because they feel the coldness of their deaths?”

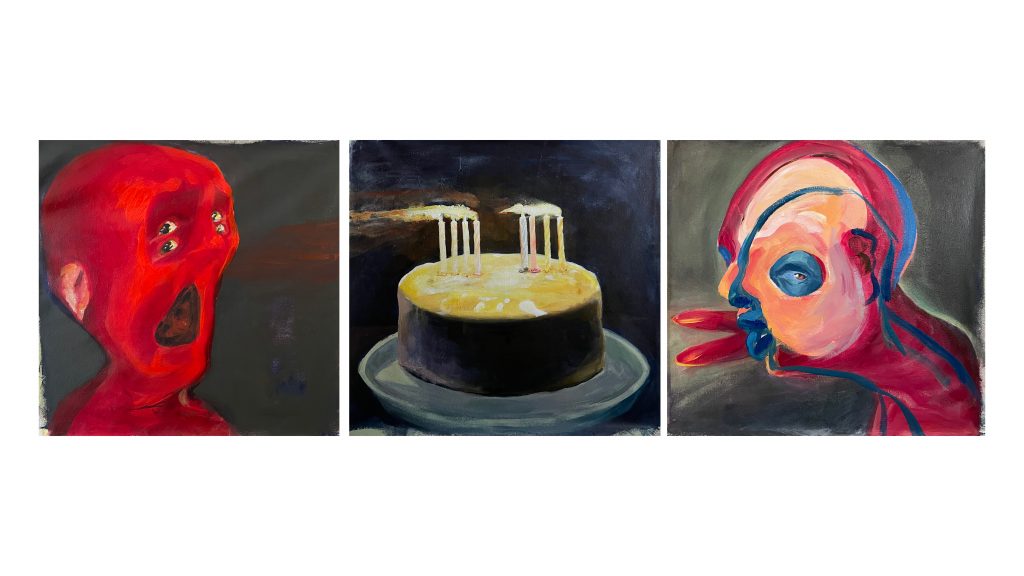

She also recalls seeing photos of children and celebrities writing messages on missiles, missiles that would later be dropped on Palestinians. They directly influenced Blow Up, the triptych she is currently painting and will be revealed at Art Rotterdam Prospects. “This act of genocide is framed as something patriotic, but it’s a form of brainwashing, indoctrinating people into horrific violence when they don’t even understand what they are part of.”

The weight of such imagery demands permanence. She turns to painting precisely because it resists this cycle. “I felt the ethical responsibility not to reproduce those images but to at least find a way to talk about them through art. Painting is about ensuring that such moments are not just a scroll, but they are here to stay – because forgetting is too easy, and denial even easier.”

With firm persistence, Bubu breaks through the heaviness of the conversation, pressing soft kisses to Diana’s lips – as if trying to comfort her. She kisses him back and whispers softly, “Habibi Bubu, I love you too.”

It’s an interruption so absurd that Bertolt Brecht himself might have written it, a moment of tenderness breaking through the weight of war, pulling us, if only for an instant, out of the frame.

Written by Emily Van Driessen

For the ninth consecutive year, the NN Art Award will be presented in 2025 to a promising artist showcasing their work at Art Rotterdam. This year’s nominees are Diana Scherer (andriesse eyck galerie), Marcos Kueh (Prospects section of the Mondriaan Fund, courtesy of Galerie Ron Mandos), Pris Roos (Mini Galerie) and Bodil Ouédraogo (Prospects section of the Mondriaan Fund). The work of the four nominees will be on view at Kunsthal Rotterdam from 15 March until 11 May 2025.

Diana Scherer is a pioneer in biotechnological art. Her work is a unique blend of botany, material research, textiles and sculpture, and is essentially a poetic exploration of the relationship between humans and nature — and the human desire to control the natural world. The balance between control and letting go plays a crucial role in her practice. Scherer is renowned for her innovative manipulation of intelligent root networks. In her studio, she creates artificial biotopes where roots are guided underground using templates. The delicate root structures that emerge from this process contain both natural patterns and human-designed motifs. By directing the growth of roots with light, soil and seeds, Scherer creates complex, textile-like structures that she uses for sculptures, installations, textile works and photography. The resulting works highlight the plant’s inherent dynamism and demonstrates how nature often finds its own unpredictable path, despite human intervention.

What sets Scherer’s work apart is her meticulous research process and the intensive collaborations she had in the past with scientists and biologists from institutions such as TU Delft and Radboud University. Her multidisciplinary approach, characterised by elements of science, nature, art, and design, enables her to render the hidden world of roots visible. This has resulted in groundbreaking techniques through which she transforms roots into ‘grown textiles’. Scherer analyses these roots at a microscopic level and she experimented with hundreds of plant species before selecting her favourites: oats, grass, wheat and maize. She likened the structure of grass roots to silk and compared the root system of daisies to wool. The artist is also fascinated by the artisanal nature of textiles and draws inspiration from traditional weaving techniques used by communities that are deeply connected to nature. Sustainability and idealism play a central role in her work.

Scherer’s practice reflects a deep fascination with what neurobiologists regard as the ‘intelligence center’ or the brain of plants. She explores ways to guide these natural growth processes, for instance by studying xylem vessels, the tissue responsible for water transport within plants. Her work reflects a fascination with hidden processes and hybrid forms, where microscopic botanical structures merge with human-made patterns — ranging from geometric principles found in nature to the imprints of bubble wrap and tire tracks. Scherer also integrates the impact of climate change on cellular tissues, incorporating elements such as burnt wood and mutated plant structures.

Scherer’s work embodies the human urge to control nature, while simultaneously raising questions about the ethical and ecological implications (and limits) of that control. In doing so, she invites us to reconsider what ‘natural’ truly means in the age of the Anthropocene.

Diana, could you tell us more about the work you are presenting at Art Rotterdam and in Kunsthal Rotterdam?

At Art Rotterdam, I am showcasing works from my ongoing project ‘Interwoven (Exercises in Root System Domestication)’ (2015–present). In the Intersection section of the fair, a monumental piece measuring 7 by 2.5 meters will be on display, suspended from the ceiling. This work, cultivated from seeds, grass and roots, was originally commissioned by Museum Kranenburgh for my solo exhibition ‘Farming Textiles’, which was presented there last year. Additionally, andriesse eyck galerie will exhibit a selection of my works at the fair.

For Kunsthal Rotterdam, I am preparing a more extensive exhibition featuring around ten larger and smaller works, some of which are intertwined with synthetic fabrics and nets, merging organic growth with human-made materials.

What are your plans for 2025?

In 2025, I will start a collaboration with the TextielLab of the TextielMuseum in Tilburg. Together, we will develop large-scale knitted fabrics and delicate, lace-like coloured nets, which I will then integrate with my root-woven textiles. While I have previously experimented with coloured fabrics, the limited availability of suitable materials has led me to produce them myself. This allows me to determine the colour, size and knitting patterns, while ensuring control over the sourcing of yarn, with the aim of working as sustainably as possible.

I will also be presenting my work in several exhibitions throughout the year. From 11 July, I will take part in ‘More than Human’ at the Design Museum in London. The SeMoCA (Seoul Museum of Craft Art) in South Korea has invited me to participate in ‘Matter Matters: Four Attitudes in the Digital Age’, an exhibition that explores how contemporary craft artists engage with materiality and technology in the digital age. My work will also be featured at the Hangzhou Triennale Fiber Art 2025 in China, while a selection will be on view in Mettingen as part of the Draaiflessen Collection. Finally, my work will be presented at the Fellbach Triennale in Germany.

How did you feel when you heard you were nominated for the NN Art Award?

I was truly surprised — it was completely unexpected. And, of course, absolutely delighted!

If you were to win the award, what project would you pursue immediately?

Winning the award would give me the freedom to focus more on research and experimentation. The further development of my current project requires both time and concentration. Additionally, I would expand my collaboration with the TextielLab of the TextielMuseum, as there are still so many possibilities to explore in combining these two forms of textiles. This year, colour research will also play a significant role in my practice.

Diana Scherer was born in 1971 in Lauingen, Bavaria (Germany) but has lived in the Netherlands for over 25 years. She initially studied fashion design in London but continued her studies at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. She has won several awards, including the prestigious New Material Award (Fellow) from Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam. Scherer’s work has been exhibited at the Frankfurter Kunstverein, the TextielMuseum, Foam Amsterdam, Manifesta, Museum Kranenburgh, the MIT Museum in Boston, the Himalayas Museum in Shanghai, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Stedelijk Museum, and at the Biennale of Sydney. Currently, her work is on view at the Cobra Museum in Amstelveen and Somerset House in London.

The winner of the NN Art Award 2025 will be announced on Friday 28 March at 20:00 in Kunsthal Rotterdam. During this celebratory evening, all exhibitions, including the NN Art Award exhibition, will be freely accessible to attending guests.

Written by Flor Linckens

Want to join a tour of the fair, led by a passionate art lover from Young Collectors Circle? You can on: Saturday 29 March and Sunday 30 March, starting times: 13.00 hours and 15:00 hours. Registration: at the Information Desk in the entrance area of the fair.

Young Collectors Circle opens up the art world to art lovers with collecting ambitions. Meet other starting collectors, get acquainted with all aspects of collecting and develop your own taste and style.

“What do we do with all those statues of controversial historical figures from the past?” Anne Wenzel asked herself. This dilemma was the starting point for her project House of Fools. During Art Rotterdam, from March 28 to March 30, 2025, at Ahoy Rotterdam, AKINCI Amsterdam will present the bust House of Fools (Johan Maurits) in Sculpture Park. Wenzel is fascinated by the way we interact with the monuments of our “heroes” from the past in the present day. Her House of Fools series is a response to the recent destruction of statues, in which statues of historical figures – due to their contentious pasts – are being pulled down from their pedestals. “With these sculptures, I show the splendour, glory, and majesty of power. With decay. From within, it seems like they have been eaten away or falling apart,” says Wenzel. The bust she made of Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen is not a tribute to this governor of the former Dutch colony in Brazil. Instead, Wenzel raises the question: what does this statue mean, as we no longer unconditionally regard Johan Maurits as a hero? In doing so, she offers an alternative to the eternal struggle between preserving and destroying monuments.

An absurd request at Art Rotterdam

“Do you want to box against me?” This question was posed to Wenzel by Deirdre Carasso, former director of the Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, at Art Rotterdam 2019. Carasso was tasked with creating a connection between the museum and the city. A boxing match seemed to her a good way to build a bridge between art and engagement. “Why don’t you ask me to create an exhibition? I’m much better in doing that,” Wenzel wondered. She accepted the challenge on the condition that, if she won, she would receive artistic freedom in the museum. Wenzel won and, in response to this “absurd” request, she depicted the many aspects of power.

Contemporary iconoclasm

The largest room in the Stedelijk Museum Schiedam was dedicated to the House of Fools series, which consisted of dark gold-coloured ceramic busts. In addition to Johan Maurits, historical “heroes” such as Jan Pieterszoon Coen and Witte Corneliszoon de With were featured, all based on statues that had recently been destroyed, vandalised, or removed. The sculpture she made of De With was purchased by Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen last year. As a sculptor, Wenzel experiences “pain” when witnessing the contemporary destruction of statues. It’s not just the disappearance of statues from public spaces that affects her, but also the fact that the work of her colleagues is being erased. In 2017, the statue of Johan Maurits was removed from the entrance hall of the Mauritshuis. This was done silently, with the statue being unexpectedly moved to the depot. The removal of the statue was seen as a sign of disapproval of Johan Maurits’ alleged involvement in the slave trade. The Mauritshuis decided to present the controversial history surrounding Johan Maurits – namesake of the museum – elsewhere in the museum, but without the statue. The Mauritshuis’ decision aligns with a trend where more and more museums and public institutions seem to choose to remove statues of controversial heroes from the past. Although Wenzel acknowledges the necessity of critically examining our own past, she questions whether such contemporary iconoclasm is the right solution. As a result, she decided to make it her new project.

The tension between decay and grandeur

The bust of Johan Maurits is full of holes, from which a greenish glaze seems to drip. His face is also damaged: “It looks like it’s been bitten by a monster, while other parts appear to have been affected by fire,” says Wenzel. The pedestal of the bust is no longer fully intact, threatening to topple over at any moment. At the bottom of the pedestal we see ceramic tiles in which footprints are printed. The sculpture thus seems to reflect its own decay. By damaging the bust, the artist seeks to challenge his impeccable image. Wenzel makes us reflect on how we deal with the memory of this governor, as part of a system of exploitation and oppression. In doing so, she shows that there are alternative ways to engage with the past.

In addition to signs of decay, the grandeur of this controversial historical hero is also emphasized. Wenzel applied a mirrored gold glaze, simultaneously confronting the viewer with their own reflection. However, the artist encountered a problem when the statue did not achieve the golden effect as she intended. The glaze proved highly sensitive to temperature, so Wenzel had to experiment with different firing techniques. At 1080 degrees, the busts remained dull black, but when she heated the kiln further, a golden shine appeared. It was the finishing touch to this series of works. Wenzel shows us: monuments are built with love – even in their decay, they deserve honour and respect.

Written by Martine Bontjes

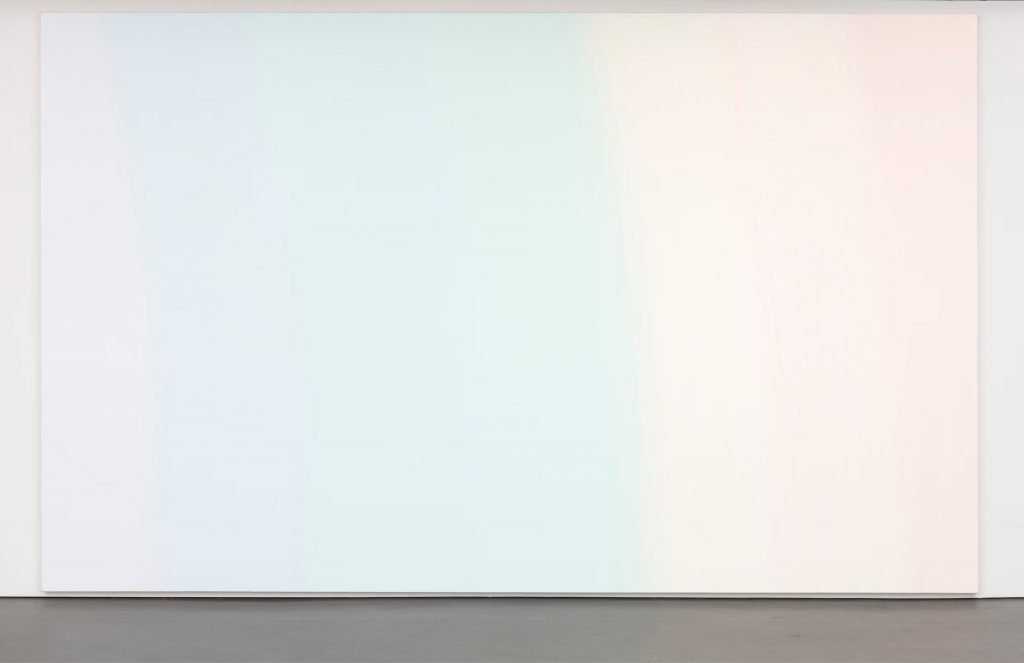

In the Main Section of the fair, the Borzo Gallery is presenting a homage to Jan Andriesse, the painter who wanted to create ‘shamelessly beautiful paintings’ and who was fascinated by the workings of light throughout his life. Averse to trends, Andriesse worked on his houseboat on the Amstel to create a body of work that was as idiosyncratic as it was consistent.

At the Borzo stand, three paintings from Andriesse’s estate are on display, alongside several Water Studies—ink drawings of light reflections on the Amstel—and new work by Andriesse’s friend and colleague Jurriaan Molenaar.

Until his death in 2021, Jan Andriesse was a key figure in Dutch painting. His best-known work is his series of rainbow paintings on large canvases, which he began on in 1994. The first rainbow was conceived for a conference room at the Council of State, but the commission was not granted. “I wondered what the most beautiful thing was that I could give the queen to look at. After months of consideration, I arrived at a rainbow. After all, what is more beautiful than a rainbow?” Despite the fact that the assignment did not go through, Andriesse decided to create the rainbow anyway, in a large format (350 x 567.5 cm). Since then, the work has been part of the collection of Museum De Pont.

With his rainbow paintings, Andriesse ventured into terra incognita. You would think there had been predecessors dedicated to painting the rainbow, but this was not the case: he was the only one. This discovery came with its own challenges, as all colours in a rainbow have the same lightness, but paint does not. To ensure the intensity of all colours was equally strong, Andriesse sometimes worked for months on end on a single painting. Every day, he would apply a new layer of acrylic paint mixed with marble powder. “If it took 200 days, that meant 200 layers. It sounds absurd, but it’s true,” Andriesse told NRC. These countless layers are not visible on the surface of his canvases, which are always smoothly polished, but only along the edges.

Partly due to the large size of the canvases—the rainbow at Museum Jan Cunen measures 190.5 x 300 cm—and the slow process, Andriesse’s legacy is not extensive. Gallery owner Paul van Rosmalen estimates that besides the Water Studies, only around ten paintings remain. Three of these are being offered at Art Rotterdam for the first time.

Andriesse’s background

Andriesse was born in 1950 in Jakarta. He spent his childhood in El Salvador before moving to the Netherlands. In 1968, he began studying at the Free Academy in The Hague and later, in the early 1970s, continued his studies at Ateliers ’63 in Haarlem. In the early 1970s, he moved to Canada and then illegally to New York, where he lived and worked for eight years. To make ends meet, he worked as a house painter in Manhattan office buildings. Reflecting in 2000, he called New York the place where he learned the most about the workings of paint and colour. “I saw the spatial effect of colour and how colour can have weight. I saw what a cold neutral white can do on a large surface and how warm white can be when mixed with pink, yellow or orange.”

On the Amstel

When he moved into his studio on a houseboat on the Amstel, he knew he had found all he needed in this place. Andriesse installed several skylights in the boat’s ceiling, allowing daylight to stream in unimpeded. This enabled Andriesse to study the interplay of paint, light and colour in detail.

The houseboat also offered views of the Weesperzijde. One evening, he saw the reflected light of the streetlamps converging at a point in the Amstel. He couldn’t believe his eyes, but consulted Marcel Minnaert’s The Nature of Light and Color in the Open Air (1937), which precisely described the phenomenon he had just witnessed. “Depending on the wind, the ripples carry the light. It is oxygen, it is space, it is change. It is continuous change. It lives; you could almost say light moves.”

Uninfluenced by trends

Jan Andriesse was a striking figure. A tall man with a sonorous voice, he preferred to dress in white. His ideas were equally as distinctive. He was a homo universalis in an era increasingly focused on specialisation. Like artists centuries ago, he made no distinction between art and science. In his view, there was as much beauty in theoretical physics as in a painting by Vermeer or Weissenbruch, two painters he admired.

He incorporated several geometric and mathematical principles into his work, such as Kepler’s Triangle and the Golden Ratio. About using the Golden Ratio, he said, “It’s a proportion that is useful for me because it naturally generates possibilities, almost outside of myself. The more my ego and neuroses are absent in my work, the better.”

Because of this absence in his work, gallery owner Paul van Rosmalen describes Andriesse’s work as introverted. Not everyone is receptive to the combination of calm and movement. You shouldn’t expect grand expressionist gestures in Andriesse’s work, but there is a sensual depth to his work. “I want to paint perfect stillness, a form of stasis as it were, without making you fall asleep, something that is still a pleasure to look at. I want to make my paintings shamelessly beautiful.”

The tribute to Jan Andriesse is accompanied by several paintings by Jurriaan Molenaar. Andriesse and Molenaar were good friends for many years. Gallery owner Van Rosmalen describes their friendship as a ‘steady and valuable artistic asset for both of them’.

Written by Wouter van den Eijkel

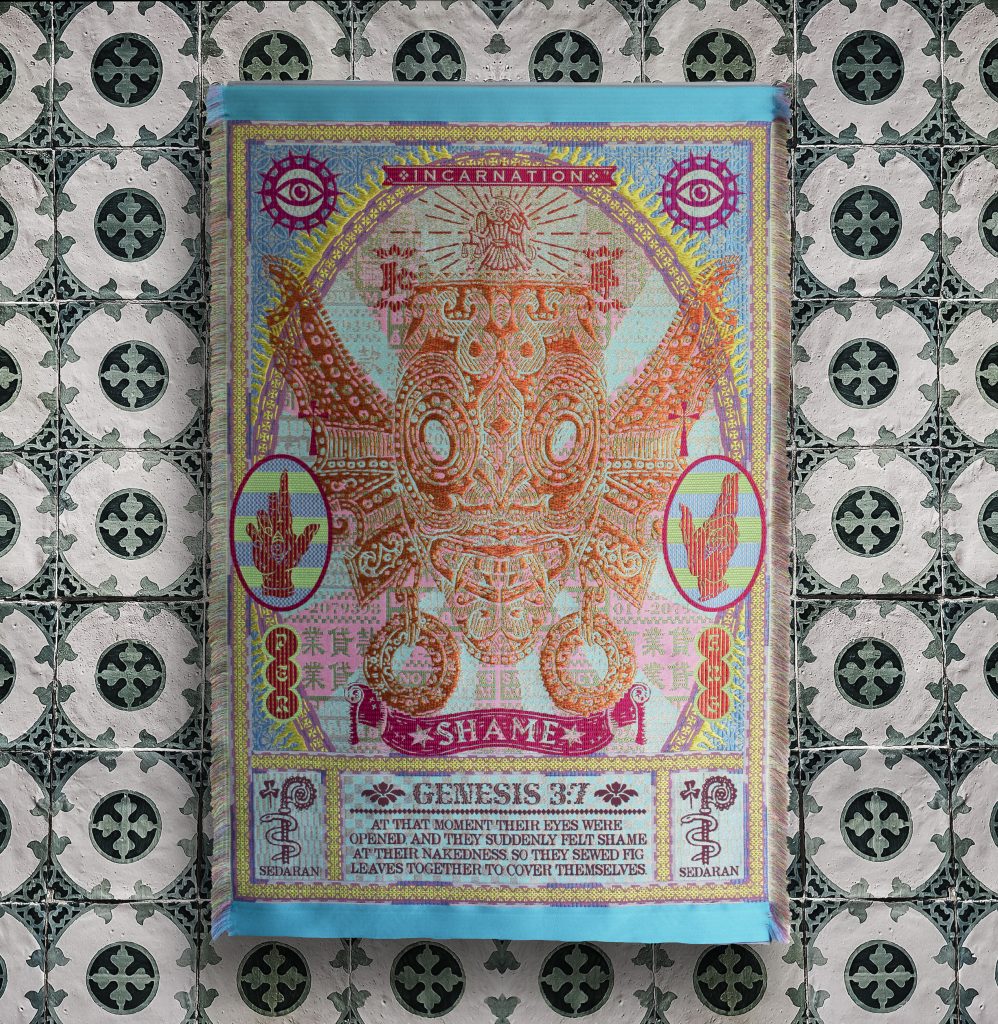

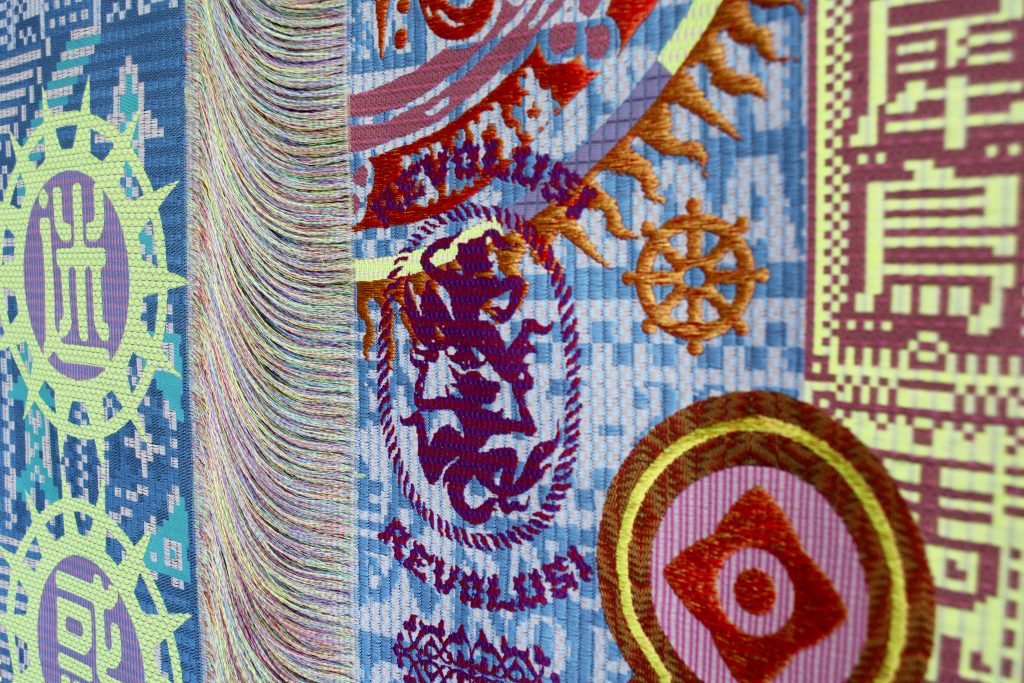

Courage, storytelling, and a profound connection to heritage define the work of Marcos Kueh (b. 1995), a Malaysian-born artist now partially based in the Netherlands. With an academic background in graphic design and in advertising, and a deeply personal journey through craft, Marcos’s woven billboards bridge ancient traditions and contemporary narratives. As a recipient of the Mondriaan Fonds grant in 2024, his installation at Art Rotterdam’s Prospects highlights the complexity of his practice; intertwining decolonisation, personal growth, and the often-overlooked sophistication of craft.

What ties your work together conceptually?

“My work is rooted in storytelling,” Marcos begins. “Growing up in postcolonial Malaysia shaped how I see the world. Decolonisation as a discourse can sometimes feel Eurocentric, as much of its academic framing emerged within European institutions. Yet the process itself was driven by the agency of colonised nations, whose voices are essential to understanding its complexities. As someone from a formerly colonised country, I find that the way we speak about decolonisation is inherently different. What language do we use to talk to ourselves, and how do we communicate our stories to others? Those questions lie at the heart of my practice.”

For Marcos, textiles serve as a bridge between past and present. “Before pen and paper, the ancestors of Borneo told stories through textiles. As a contemporary weaver, I see my work as an extension of that legacy, speculating on what stories I want to leave for my generation and the next.”

How did your journey into textiles begin?

“My background is in graphic design and advertising, but I’ve always been fascinated by local visual culture. Textiles, in particular, carry immense storytelling potential. Initially, I approached them purely academically, researching their history and cultural significance. I worried whether society – and especially my family – would accept me as a textile artist. In Borneo, textiles are often associated with the underprivileged, and pursuing them felt risky.”

The turning point came in the Netherlands, where he transitioned from studying textiles to physically working with them. At the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague, he discovered a textile workshop and visited the TextielMuseum. “For the first time, I truly understood the craft’s complexity. Using the loom involves intricate problem-solving: calculating tension, designing patterns, even understanding chemical dyes. It shifted my perspective: people from the villages are far from primitive; their systems are incredibly sophisticated. That realisation changed how I see craft, but also myself. I stopped feeling like I had to apologise for where I come from.”

How does decolonisation influence your practice?

“When I first discussed decolonisation at school, I’d often break down crying,” Marcos admits. “The topic is academic, but for those of us who’ve lived through these systems, it’s deeply personal. That emotional weight influences not just how I speak about decolonisation, but how I present my work. It’s layered and invites different interpretations. Some people see beautiful textiles, others engage with the deeper stories.”

For Marcos, hospitality is another lens through which he explores decolonisation. “Being hospitable is a craft. How you treat someone, host someone, it’s a skill. In my work, I think about who I’m hosting in this conversation and how I use language to include them. Different cultures view the world and its stories differently, and I want my work to reflect that generosity.”

How do you balance traditional craft with contemporary concepts?

Marcos sees parallels between indigenous practices and modern systems like capitalism. “In traditional cultures, there’s a time for everything; for example stories of harvest, life, death. It’s similar to how campaigns work in advertising. You assess when a story needs to be told and how it can have the most impact. I often compare these practices in my work to show how they intersect.”

This duality is reflected in his installations, where textiles – his woven billboards – are often suspended from ceilings. “It’s like walking through a rainforest,” Marcos explains, “but instead of leaves and trees, you’re surrounded by woven advertisements. It’s a playful reimagining: what if Borneo, not New York, were the cultural epicentre of the world?”

Why do you often suspend your work above eye level?

“That’s such an interesting question. I’ve never thought about it before,” Marcos admits thoughtfully. “In many museums, artworks from colonised cultures are displayed at eye level or below, framed as curiosities rather than celebrated as cultural treasures. My decision to suspend my work might have been a subconscious response to that dynamic.”

Many of his installations culminate in a large woven poster suspended like a waterfall, inspired by Borneo mythology. “In the ancestral stories of Borneo, it is said that our ancestors descend to earth through waterfalls to visit the living,” Marcos shares. By asking people to look up, I’m inviting them to shift their perspective, to see these stories and their heritage with new respect.

How has the Mondriaan Fonds grant influenced you and your work?

“The grant gave me courage,” Marcos says. “In postcolonial countries, we’re taught to be cautious about resources, opportunities, about everything. This grant felt like approval to create freely. It’s emotional, too. Art isn’t just about resources; it’s about emotional readiness. When someone believes in you, it pushes you to do your best, not just for yourself, but for society.”

What will you be showing at Art Rotterdam?

“At Art Rotterdam’s Prospects, I’m presenting an installation originally created for Manifesta 15, where it was exhibited in a 17th-century church in Barcelona,” Marcos explains. “Growing up in a postcolonial country, I questioned whether my interest in Christianity was driven by faith or by the desire to align myself with Western ideals. The installation is a deeply personal reflection of that struggle. It’s a split work, divided down the middle, representing the constant internal negotiation of identity as a postcolonial subject: the tearing between acceptance and rejection, the feeling of being incomplete. Positioned in front of the church’s historic religious paintings, it also served as a confession to the Church: ‘With the faith you brought us, we still struggle.’”

Written by Emily van Driessen