Coming soon

Coming soon

Select type

AKINCI will present work by Lungiswa Gqunta at Art Rotterdam. In her practice, the South African artist explores the elusive world of dreams. She sees these dreams as a place where important knowledge can be gained that is overlooked or excluded in other places. Her work was recently on display at the Liverpool Biennial, at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin and at the Centraal Museum in Utrecht and earlier this year, she was invited to submit a proposal for the famous High Line in New York.

In her multidisciplinary practice, which includes performance, installation, sculpture and printmaking, she draws attention to the complex and ongoing ways in which colonialism and patriarchy shape South Africa’s contemporary political, cultural and social landscape — and continues to create systematic inequality until this day. She highlights, among other things, African systems of knowledge and belief that were structurally excluded during the apartheid regime.

In her most recent work, Gqunta explores the concept of sleep and dreams on the basis of her Xhosa heritage. Dreams function as a connection with her ancestors and are a place where knowledge can be gained. Her multi-sensory and layered work is informed by this dream world and explores themes such as landscape, violence, resistance, collective healing, identity, female power, the domestic space, traditions and rituals, history and collective memory, privilege, globalisation and capitalism. Recurring materials in her work are materials that could also serve as a weapon in a different context or form, such as glass, concrete, barbed wire and more specifically: the more aggressive razor wire. They are symbolic and emotionally charged materials that refer to the townships, which were reserved for the black inhabitants of South Africa during apartheid. Gqunta also regularly uses white sheets in her works, which refer to a recognisable ritual: the processing of the laundry and the folding of the sheets, traditionally a moment when knowledge was shared between the female members of her family, but at the same time a potential moment for secret talks and resistance during apartheid.

Her recent solo exhibition ‘Sleep in Witness’, that was on display at AKINCI this autumn, was previously presented in a different form at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds. In both exhibitions, part of the floor was covered with cracked clay and sand, carefully shaped by the artist’s feet. As a viewer, you were forced to walk over it in order to enter the exhibition, which made the instability under your feet tangible. In combination with blue structures of transparent, hand-blown glass — reminiscent of rocks or water — they formed the site-specific installation “Zinodaka”. The video work “Rolling Mountains Dream” in the exhibition referred to remembering and learning from dreams. And the works “Instigation in Waiting I & II” referred to the ways in which colonial oppressors introduced new plant species and removed existing ones as a way of controlling the environment, a tradition that lives on in a different form in conservatories and botanic gardens.

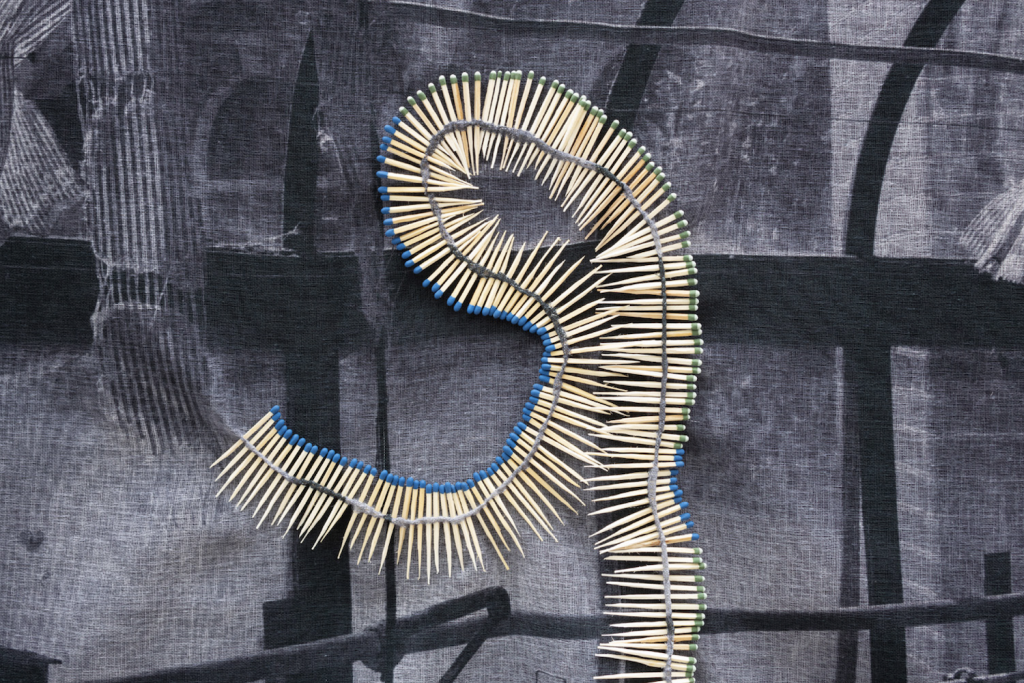

Her room-filling installation “Ntabamanzi”, which consists of wave-like barbed wire wrapped in bright blue fabric, was on show in the Centraal Museum this summer. The large-scale work refers to the reclaiming of healing water rituals that were prohobited during the apartheid regime, but it also challenges the viewer to think about freedom of movement in a space — and how that is not as self-evident for everyone. The name is a combination of two Xhosa words: ntaba (mountain) and manzi (water) and the installation was born in a dream of the artist. Gqunta then worked for months on the execution of the work, after which only the sharp parts still portrude.

Gqunta isn’t afraid to ruffle some feathers and creates installations that cause discomfort and confrontation in white viewers, while other works offer care of the mental health of black viewers. She feels that it’s important to have certain conversations, no matter how uncomfortable they may be. In a video for the Henry Moore Institute, she states: “I think of it as like trapping someone into a conversation. No one’s gonna go willingly to a place that is difficult, that is hard, and so you gotta reel them in. The aim is for the work to follow people home somehow. To haunt them. [Some of my other] installations are I guess the complete opposite, where it’s about rest and recharging.”

Gqunta studied sculpture at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University in Port Elizabeth, followed by a master’s degree at the Michaelis School of Fine Arts in Cape Town. She completed residencies at the prestigious Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam, Gasworks in London and Dumbarton Oaks in Washington DC, a research institute, library and museum affiliated with Harvard University. She currently lives and works in Cape Town. Her work has been shown in the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, during Manifesta 12 and the Istanbul Biennale and has been included in the collections of institutions such as KADIST in Paris, the Kunsthaus Museum in Zurich, the Centraal Museum in Utrecht and Zeitz MOCAA – Cape Town Museum of Contemporary Art.

Written by Flor Linckens

At Art Rotterdam, you will spot the work of hundreds of artists from all over the world. In this series, we highlight a number of artists who will show remarkable work during the fair.

Last December, the Belgian newspaper De Morgen presented a list of the 10 most exciting exhibitions in Belgium in 2022. The entire programme of the young Pizza Gallery in Antwerp was singled out for praise by the three art journalists behind the article, but they paid particular attention to the solo presentation of Jonas Dehnen. At Art Rotterdam, the work of the German artist will be on display in the New Art Section.

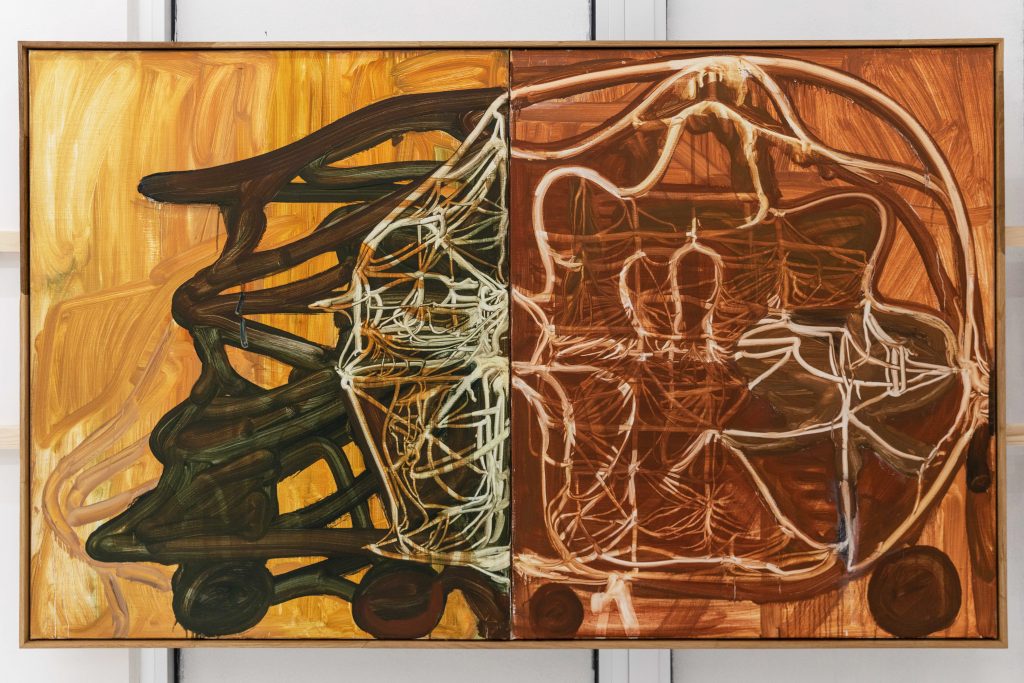

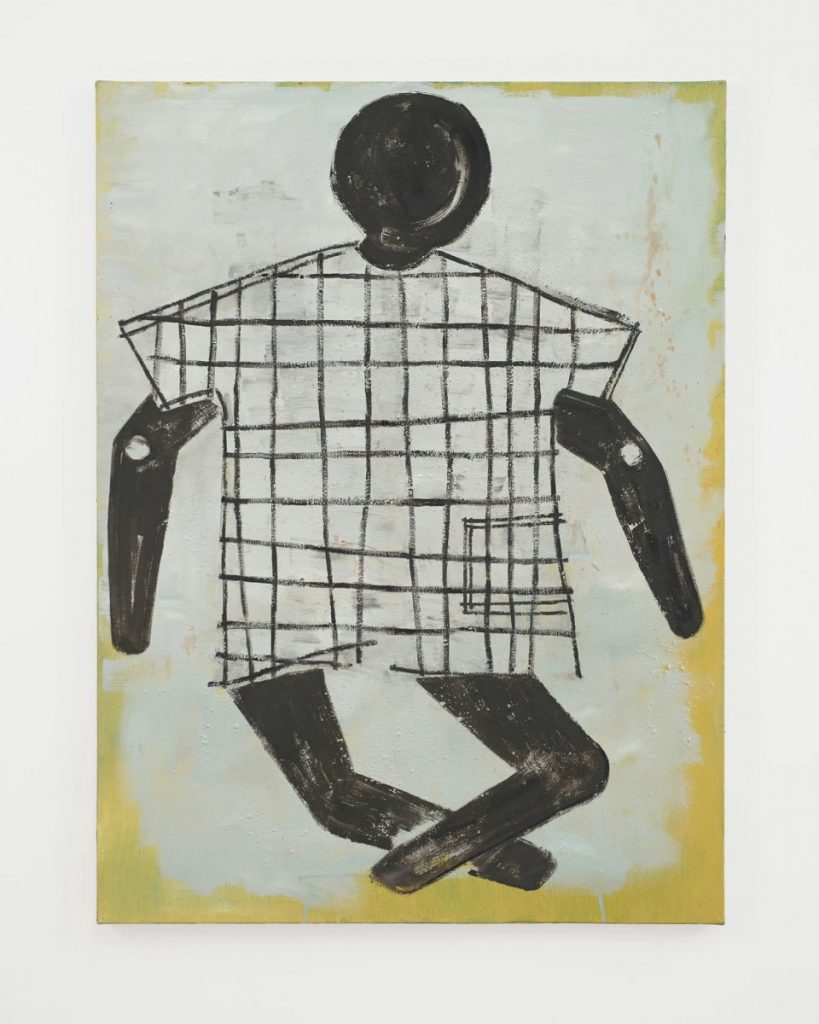

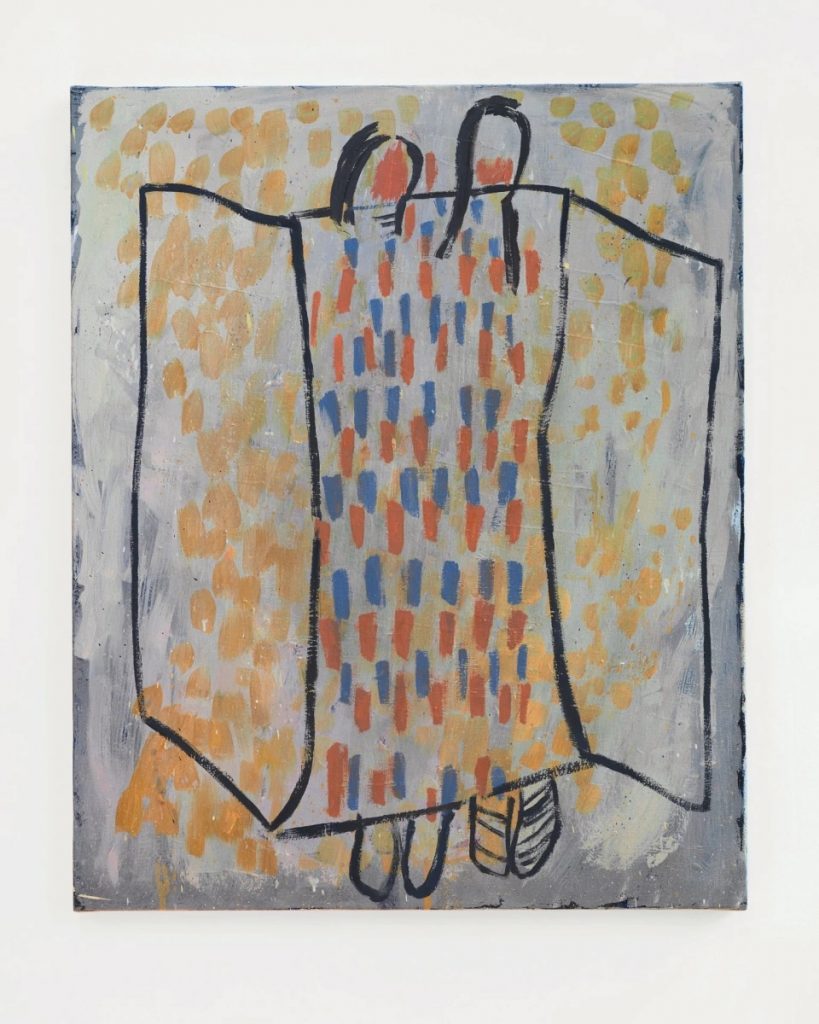

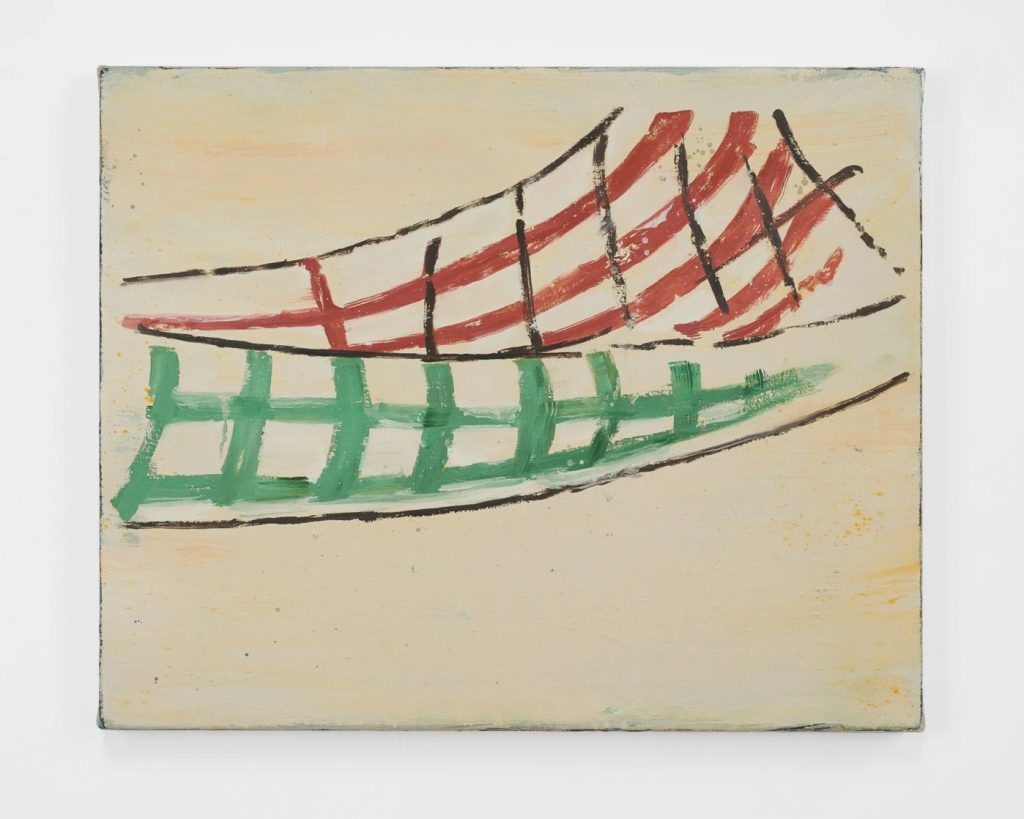

Painting and drawing are central to Jonas Dehnen’s practice, but he also creates installations and sculptures, depending on specific exhibition contexts. Dehnen takes much of his visual raw material from the communities amongst which he grew up. He spent his formative years in both Germany and the United Kingdom, and has now been living in Belgium for several years. The artist is fascinated by the way in which communities construct a visual identity using symbols and traditions, from pub signs to carnival floats, from vernacular architecture to folk paintings, and other elements of what could be called ‘visual patois’. Which role is reserved for the collective and which for the individual, within that mechanism? And how does globalisation fit into that? Dehnen abstracts, fragments and re-combines different signifiers in his paintings, creating new characters and idiosyncratic protagonists. The pictures emerge from a prolonged process of trial and error: Layering, erasure, additive and subtractive painterly gestures, and the repurposing of underlying image fragments.

At Art Rotterdam, Dehnen presents a series of paintings that derive their imagery from romanticism in a broad sense. E.T.A. Hoffmann’s ‘Der Sandmann’ serves as a source for motifs, such as a mechanised eye, hands and wheels. These enigmatic structures and circuitries hint at designs for a primitive automaton. They also offer veiled visual references to past works in the artist’s oeuvre, and to paintings that hung in his childhood home, thereby establishing feedback loops of painterly gestures and ideas. There is an entanglement between the physical material of the work, and the image that took shape within it. Thinking and doing collapse into one another to become a singular mode of being in the world. The works are maps of themselves, map and territory both, thought-maps looping back into themselves in an infinite regression. At times the paint is applied as though to a location on a flat surface, and at other times at a certain depth within an image. The flatness of the object and the artifice of a painted picture are continually toyed with.

In 2019, Dehnen obtained his master’s degree in painting at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (KASK) in Ghent, under the tutelage of Vincent Geyskens. Previously he completed a bachelor’s degree in fine arts at the University of Lancaster, UK. After graduating, Dehnen was invited for a residency at FLACC in Genk and last year, he was nominated for the PrixFintro Prize, for which he shared second prize. His work has been exhibited at Z33 House for Contemporary Art in Hasselt, claptrap in Antwerp, and Social Harmony in Ghent, among others.

Flor Linckens

No man is an island: artist Klaas Rommelaere turns family and friends into art

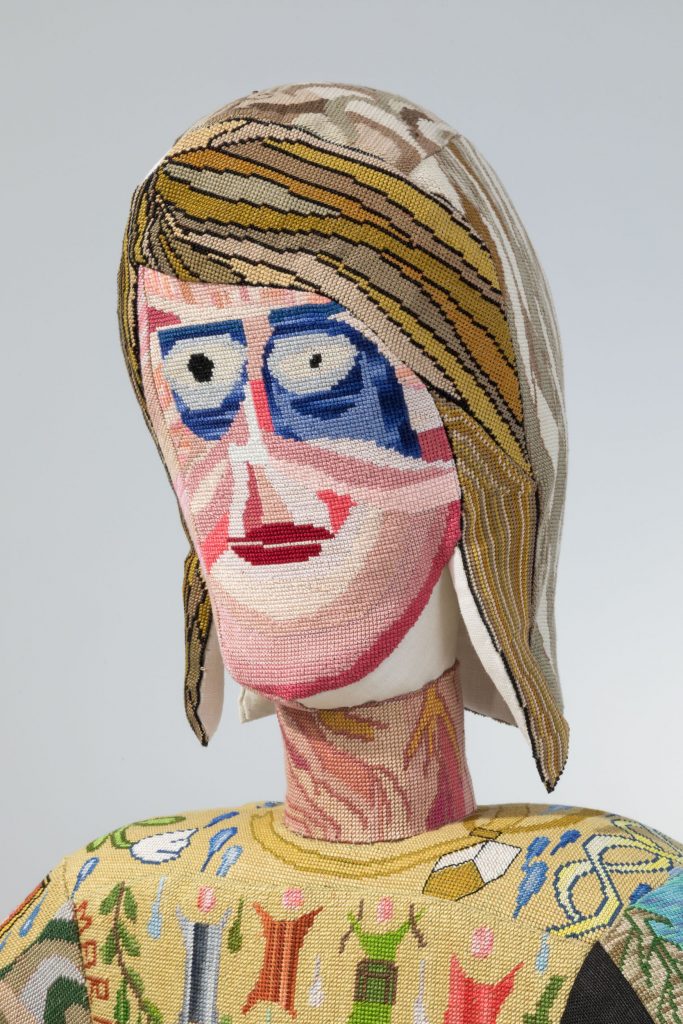

Artist Klaas Rommelaere is currently causing a stir with his Dark Uncles series, consisting of a parade of life-sized embroidered dolls of family and friends. For Art Rotterdam, Rommelaere made no fewer than ten new works to be displayed at Madé van Krimpen’s booth. “I am a loner. The paradox is that my work almost always involves people. I’ve even made them in doll form.”

Rommelaere (Belgium, 1986) studied fashion at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent. During his studies, he did internships with Henrik Vibskov and Raf Simons, but soon realised that the fashion world was not a place where he could act on his ideas. Inspired by films, comics, books and personal experiences, Rommelaere began translating his ideas into visual work using the tools and materials he knew best: the needle, thread, wool and yarn.

Do you already know which works you will be showing at Art Rotterdam?

At Art Rotterdam, I’ll be showing works under the name of Dark Uncles. This is a project that started a few years ago when I came up with the idea to create a procession with people who have influenced me over the years, from family to friends. They wear embroideries of memories and photos and are completely covered with embroidery. The project has already been shown in Belgium, France, Germany and the Netherlands, with a different set-up each time. For Art Rotterdam, I made ten new works. I always find it interesting to work on an idea and see how far you can take it.

For those who don’t know your work: you create works of textile, embroidery or in the form of life-sized dolls. Why have you chosen this medium?

I became familiar with embroidery and handicrafts during my fashion studies. That study programme was my second Bachelor’s and Master’s and I was looking for an easy and direct way to convert my graphics into textiles without too much cost or hassle. So, as early as my first year, I began embroidering with wool and canvas from a local thrift store. In the years after that, I began exploring another technique. This is how my artistic process has evolved, which also fits my way of thinking. Handiwork takes a lot of time, and that time lets me think about my work and how it will end up. It’s like building a house: you lay brick by brick and in the end, you have an entire house or work of art. Completing a work or project can take anywhere from six months to two years.

You’ve titled the series Dark Uncles, a Swiss folklore term for doubles. It consists of life-sized dolls of family and friends. Why did you make the people in your immediate environment the subject of your work?

When I began working with canvas and flags, my grandmother always took care of the finishing touches. This was in Ingelmunster and a little ways down the road, there was a beautiful white wall where I always took pictures. The cloth always had to be carried like a flag to that location. My grandfather and a neighbour usually did this. I also took pictures of that little procession and always found it to be a strong image. As I’ve grown older, I sometimes enjoy looking back to see how far I’ve come and which people have influenced me. We’re so obsessed with moving forward these days that we sometimes forget our roots. No man is an island.

I’ve read that as many as 100 people have contributed to the Dark Uncles series. How does such a collaboration come about and where do you find so many people who are willing to embroider for you?

The first part of Dark Uncles was made entirely during the pandemic. At first, the idea was to do everything in workshops, but then the pandemic started. That’s why the museum made a call for volunteers who wanted to embroider. Many people were at home with a lot of time, so the response was massive. We sent everything by mail. I was in contact with them by WhatsApp and email. I did not see most of the people who helped out until the opening. From this project, a new group of ‘madammen’ has emerged, in addition to my first group in Merksem and Ingelmunster.

Embroidery takes a lot of skill and time. It is certainly not a fast technique. Do you consider your work a criticism of the fast-paced art world and our society in general?

It’s not a criticism because I didn’t consciously choose it. It’s just how I work. But I do think it feels different to people who see the work because it is something tangible, something practical and you can tell it has been created with care, time and skill. Visitors are always amazed because it looks different in real life than in pictures due to the details and texture of the canvas. Since it takes so long to finish a work, I can put in a lot of details, so that you cannot ‘read’ the work completely at a single glance. I often hear from people who have my work hanging in their homes that they see something new almost every day.

I read that you are inspired by cult films. Which films and why do these particular films appeal to you?

I try to see all films that are shown in cinemas and luckily, I have a subscription. Usually, it is the atmosphere of a film that appeals to me most. When I’m working on a project, I’m open to things that can ‘feed’ the project and make it stronger. When I was creating Dark Uncles, I travelled to Tokyo and became fascinated with Hayoa Miyazaki (co-founder and artistic director of the famous Japanese animation studio Ghibli, ed.). I’ve watched documentaries about him and read his biography and have learned that we think exactly the same way about life and the artistic process. I believe film is the ultimate art form.

Would you say that the main theme of your work is the relationship with your immediate environment?

I’m not much of a social person. I like to be alone and only need a few people who I see regularly. Apart from that, I’m a loner. The paradox is that there are almost always people in my work; I’ve even made them in puppet form. I think my work is a way to communicate with people, to feel connected to the ‘world’ as it were.

Wouter van den Eijkel

Salim Bayri – The MC of collision

What happens when opposing situations, technologies and cultures collide? Salim Bayri creates such collisions all the time, and often with a smile. With the digital environment as his point of departure, his work takes on various forms. You might call him the MC of the cultural-technological clash. Bayri has been nominated for this year’s NN Art Award.

In search of the core

Salim Bayri (Casablanca, Morocco, 1992) won the Volkskrant Visual Arts Prize last autumn. He was nominated by writer and jury member Abdelkader Benali, who praised him for his versatile and elusive body of work. Benali hits the nail on the head, as the core of Bayri’s work is difficult to define. “You sort of walk around it,” Bayri said in a recent interview with the magazine Mister Motley. “It would also be a failure to seize it as it were, because I would then be destroying the work and I don’t want to do that.”

Finding a core is also difficult because Bayri can rightly be called a multidisciplinary artist. He creates videos, installations, wearables, apps, drawings, digital prints and more. Bayri usually starts with a digital drawing, but is not very interested in the differences between online and offline expression. His interests are broader. “In essence, he allows opposing images, situations, technologies, cultural practices and phenomena to collide and then looks at the result with a smile. That creates a striking openness in all kinds of respects,” says Bayri’s gallery owner Kees van Gelder.

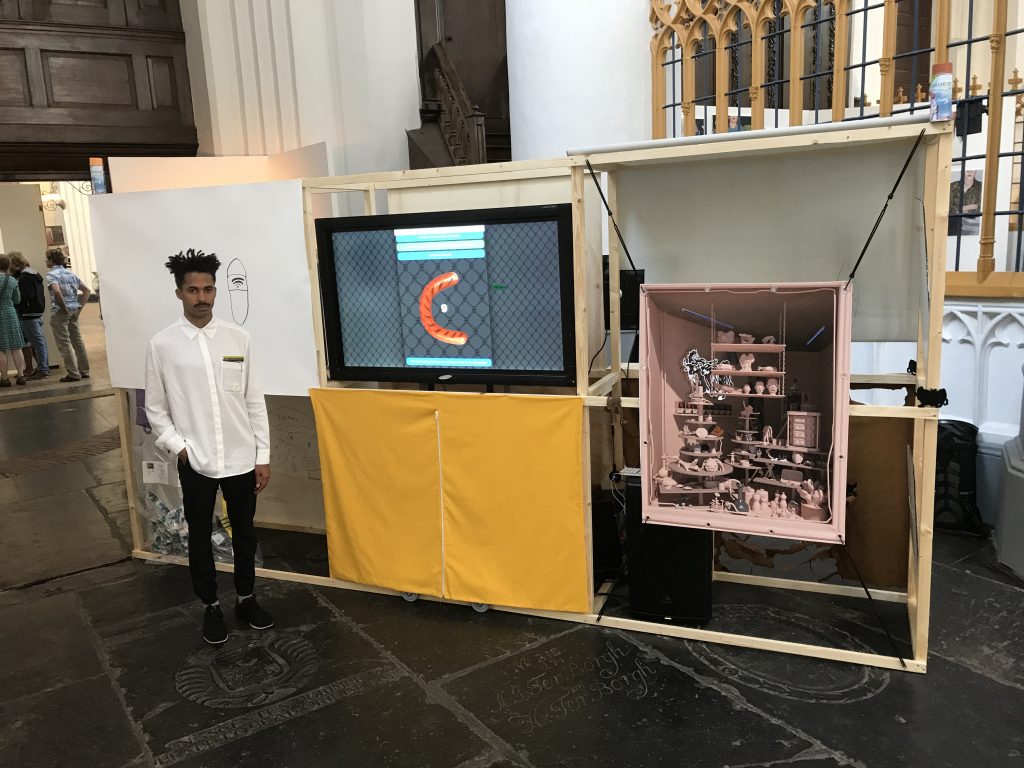

Van Gelder first came across Bayri’s work in 2017 when he visited Kimball Gunnar Holth’s graduation show in Groningen’s A-kerk. He was immediately sold. “Salim stood in front of his installation/scaffolding, which he called ‘Smartshop’, and sang towards the sculpture through an amplifier in Arabic, Dutch, French and Spanish, improvising descriptions of what he literally envisioned. The singing tone was clearly the North African multi-tone of the Maghreb. A fabulous presentation.”

Van Gelder is not the only one who has noticed Bayri’s work, given that his work is guaranteed to attract a lot of attention. Since completing his residency at the Rijksakademie, it has already been shown in the Netherlands at CODA, Framer Framed, W139, La Capella in Barcelona and Fondazione Merz in Turin. In addition to the Volkskrant Visual Art Prize, Bayri also won the Charlotte Köhler Prize awarded by the Prince Bernhard Culture Fund last year. At the end of January, Dead Skin Cash, a duo exhibition with Ghita Skali, will be opening in W139 in Amsterdam, where visitors can sell dead skin cells for money.

Code switching

Considering his background, the fact that toying with context, conventions and expectations is Bayri’s second nature is hardly surprising. Bayri grew up in Casablanca, where he attended a Spanish school. “I constantly heard Arabic and French all around me, while everything online was in English. As a young boy, I learned about Carlos II at school, after which I walked home along streets where everyone spoke Darija, and once at home, heard about the price of baguettes in French news. In my head, I switch constantly, searching for the common denominator.”

He went on to earn a Bachelor’s degree from the Escola Massana in Barcelona, a Master’s degree in Media, Art Design and Technology from the Frank Mohr Institute in Groningen and did a residency at the Rijksakademie, where he ultimately made a presentation similar to the one in the A-kerk in 2020.

Sad Ali

The most famous example of an object Bayri places in a different context is his alter ego Sad Ali, short for Sad Alien. It is no coincidence that the word Alien is a homonym that can refer to an alien life form as well as someone from another country. Sad Ali is a wordless, sad cartoon character who regularly appears in Bayri’s work and originated as a digital drawing, a computer file.

In terms of design, Sad Ali is like something straight out of a Pixar movie. Like cartoon characters, Sad Ali is a hollow shape. He has no heart, bones or brains. “So, these shapes are like containers. Everything that moves on the screen is hollow. Sad Ali is also empty; it doesn’t talk or say anything and has no agenda of its own. But there it is, and its presence is so fragile that it becomes the elephant in the room,” says Bayri. The latter is evident from the diverse reactions that Sad Ali elicits from visitors. While one visitor laughs about it, the other finds him terrifying.

ChatGPT’s analogue counterpart

For many people, the self-learning chatbot ChatGPT is a fantastic tool. You can ask the chatbot almost any kind of question and receive an answer in a complete sentence. But for an artist who toys with conventions and works from a digital environment, it is nothing short of a godsend.

In addition to a presentation of his Smartshop, Bayri has also considered presenting an analogue counterpart to the chatbot at Art Rotterdam. He originally intended for gallerist Van Gelder to sit in a chair in front of a white wall and hand out sheets of paper, each with a different question. “Unfortunately, there was not enough room for this on the exhibition floor, but Bayri is looking into possibilities to do something similar,” says Van Gelder.

Wouter van den Eijkel

At Art Rotterdam, you will spot the work of hundreds of artists from all over the world. In this series we highlight a number of artists who will show remarkable work during the fair. During Art Rotterdam, Upstream Gallery will present work by Noor Nuyten, Kévin Bray (who was nominated for the NN Art Award), Frank Ammerlaan and Marinus Boezem. In their practice, these artists all explore a connection between material, physical worlds and immaterial or digital worlds. Experimentation in terms of materials and techniques plays a significant role in that.

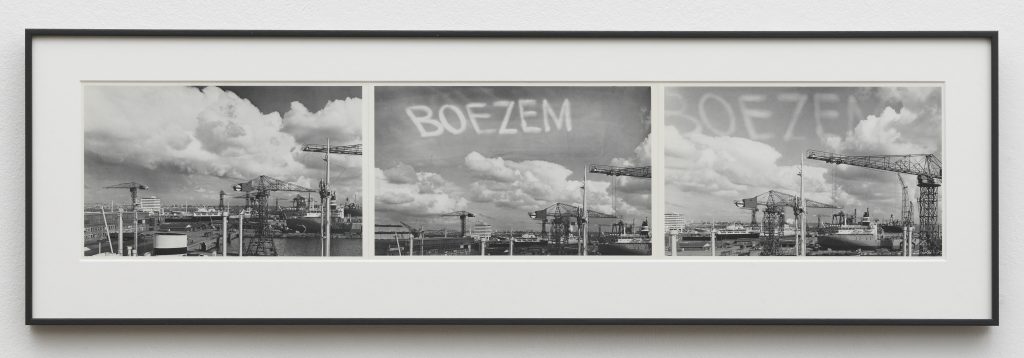

Marinus Boezem (1934) is considered to be one of the most influential Dutch conceptual artists of the past century, alongside Ger van Elk and Jan Dibbets. In the 1960s, Boezem discovered the artistic potential of elusive elements such as air, weather, movement and light, resulting in a series of exciting, intelligent and immaterial works that often contain a powerful, poetic and humorous charge.

His work “3 Seconds of Dutch Light” from 1976 offers a striking illustration. Most people will think of 17th century paintings when they hear the term ‘Dutch light’. Boezem offered a more conceptual twist to the genre, when he exposed a sheet of photosensitive photo paper to Dutch light for three seconds, after which he mounted it on an aluminum plate. Three full seconds of light, however, will result in a completely monochromatic black sheet of paper. The 17th-century painters who traveled en masse to our coast may have managed to capture a representation or interpretation of light, but Boezem’s work actually captures Dutch light — as a material or ingredient, even if it is no longer visible to the viewer.

The idea is central to Boezem’s practice, alongside a curious imagination. This means that he works in a multitude of materials and disciplines. In 2021, the Kröller-Müller Museum presented his ‘shows’, based on a series of fifteen drawings that he made between 1964 and 1969. These are conceptual blueprints for installations that could possibly be realised. Boezem sent them to art institutions or presented them in person. Some concepts were implemented at the time, other sketches first found a physical form in the exhibition at the Kröller-Müller Museum.

Boezem wants to make art that is close to life, in part because museums do not always invest in their relationship with (and relevance within) society. In 1969 he was co-initiator of the rebellious and leading exhibition ‘On loose screws’ in the Stedelijk Museum. One of the works he exhibited was “Bedding”, for which he hung pillows and sheets from all the windows of the museum. With a wink he symbolised both a breath of fresh air through the museum and a recognisable household tradition. At the same time, Boezem manages to make something immaterial visible: a breeze. Moreover, the artist effectively blurs the boundaries between the almost sacred museum space and the public space, presenting art as a bridge between the museum and society.

Boezem would later make several works of art for the public space. His “Green Cathedral” in Almere was voted the most popular outdoor artwork in the Netherlands — wedding ceremonies are even performed there. The work consists of 174 Italian poplars that form the floor plan of the Notre-Dame cathedral of Reims, true to size. A little further on, the exact same shape has been removed from a wooded area, reshaping the floor plan of the structure, but now in negative space. The cathedral is a recurring element in Boezem’s oeuvre and the artist also joked that a new city, rising from the polder, deserved a cathedral. Other recurring themes in his practice include the universe and cartography.

Boezem’s conceptual work is also related to the arte povera of the 1960s and 1970s, an originally Italian art movement in which artists resisted the commercialisation of the art world, among other things. On the one hand, materials were chosen that represented no financial value — such as earth or twigs — and on the other hand, the often perishable or immaterial art of these makers was sometimes difficult to trade as a commercial product. The movement was extremely influential, with significant parallels in other international art forms of the time; from land art and minimal art to conceptual art.

Boezem’s work has been exhibited at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, the MoMA, the Brooklyn Museum, the Van Abbemuseum, Kunsthalle Bern, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, the Hamburger Bahnhof and the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, among others. His work has been collected by institutions like the MoMA, Museum Voorlinden, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, the Stedelijk Museum, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen and the Kröller-Muller Museum. During Art Rotterdam, the work of Marinus Boezem will be on display in the booth of Upstream Gallery.

Flor Linckens

During Art Rotterdam, NN group will present the NN Art Award for the seventh time: to a contemporary art talent with an authentic visual language and an innovative approach. NN Group has been a partner of Art Rotterdam since 2017 and has been awarding an incentive award every year since then. An annually changing jury of art professionals makes a selection of four promising talents, from which a winner is ultimately chosen. The conditions are clear: it concerns artists who have been trained in the Netherlands and who show their work during Art Rotterdam. NN Group will purchases one or more works from the nominees for its corporate collection. Last year, the NN Art Award (worth €10,000) was won by the Lithuanian artist Vytautas Kumža. We’ve interviewed him to find out what winning the prize has meant to him and how he has experienced the past period.

How did it feel to win the NN Art Award?

Vytautas Kumža: “Honestly, I was really surprised to win the NN Art Award. I had known work by other nominees for years and it was just great to be included in such an impressive group of artists and to present artworks together. I was the youngest of the group, so it felt great that the jury believes in me and sees the importance of continuing my practice — and that they are also supporting it with this award.”

What has the past year been like for you?

VK: “The past year has been really intense and productive. I had a busy season and many art fairs, new works were presented at June Art Fair in Basel, Art Dubai, Enter Art Fair, Unfair and I have ended the year with a solo exhibition in Vilnius. I feel like I did develop a new way of working last year even though it was quite a full year.

I have traveled quite a lot during the past year and every place I visit leaves an impression or aesthetic in my mind. In my work, I don’t photograph people, because I’m more interested in gestures that people leave behind. So what is happening and what I see around me certainly leaves traces that are later translated into my practice, sometimes in a more subtle or direct way.”

How did the works that you showed during Art Rotterdam come about? Do you follow a specific process?

VK: “The series of works that I presented in the NN Art Award booth was inspired by the imaginations of people, that were created as a result of the recent times and its stories-flooded screens; in which urban spaces were taken out of social relations. I have noticed in the world of the post, the new form of imagination was gaining momentum, but its contours were blurring. By rethinking various everyday processes, I constructed photographic and glass constructions of found objects and memories and created several possible scenarios that deceive the gaze and question the logic of its view of the viewer. With this confusing instability I ask the question: ”Can observation change the nature of things or give them a different meaning?”. While leaving visible “seams and edges” in multi-layered photographic plans in the same way as lead sealed glass pieces, I created seamless stained glass constructions. This transparent obstacle, between the print and the viewer, becomes an indicator that we are looking through one’s constructed ‘filter’ of vision.”

Are there any particular things you were able to achieve thanks to the prize money?

VK: “I was able to create and produce a lot of new artworks, so all the prize money was invested in that. There wasn’t even a question of where and when it should be spent, so I did it with confidence and I’m really glad I didn’t have to think too much about it, that I could just do it and see the result, which in the end I was happy about. In the past year I have started to experiment more with different ways of incorporating glass and combining it with other objects. I have also expanded my practice in a more sculptural way. And I’m glad that there were a lot of opportunities to present it last year. During Art Rotterdam 2023, some of the most recent works will be presented, followed later in the year by a solo exhibition at the Martin van Zomeren gallery.”

What is your ultimate piece of advice for young artists?

VK: “It’s a tough question because there isn’t one ultimate piece of advice, because everyone needs something different and has their own unique path. Although I would just say to just keep making work and to not stop, even if it sometimes seems impossible to do so. I believe that as an artist, you have to get used to ups and downs in every stage of your career. It’s just a matter of making your practice a part of your routine and taking it seriously, while being open to mistakes, accidents and suggestions.”

Interview by Flor Linckens

During Art Rotterdam, you will see the work of hundreds of artists from all over the world. In this series, we highlight a number of artists who will show remarkable work during the fair.

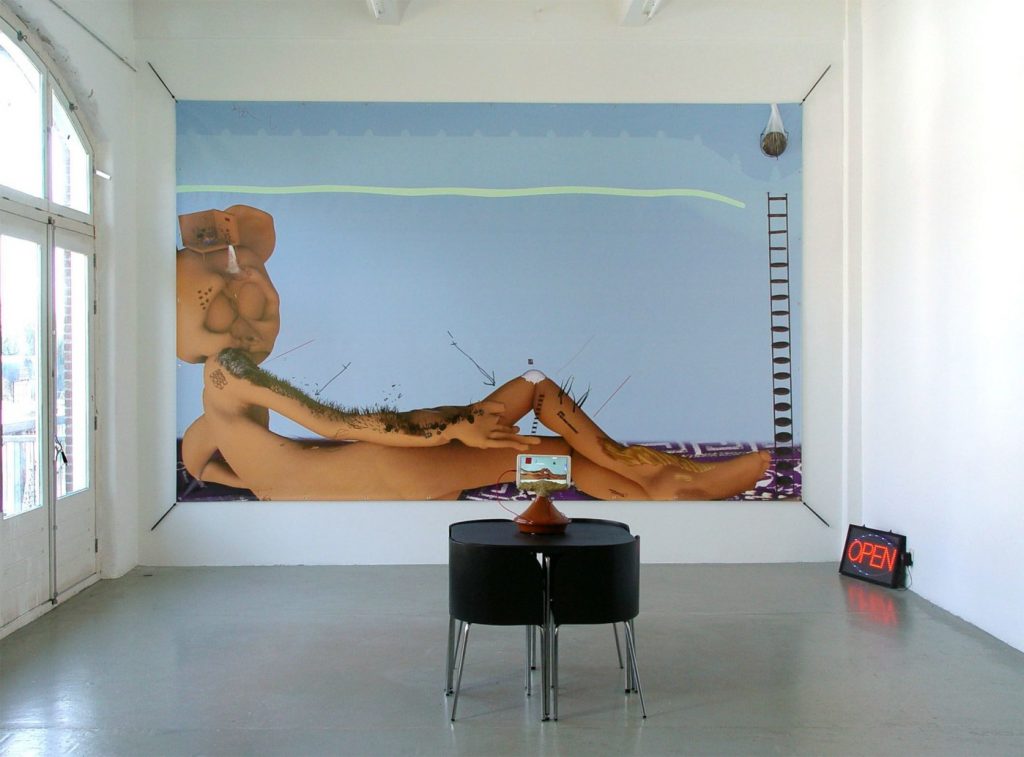

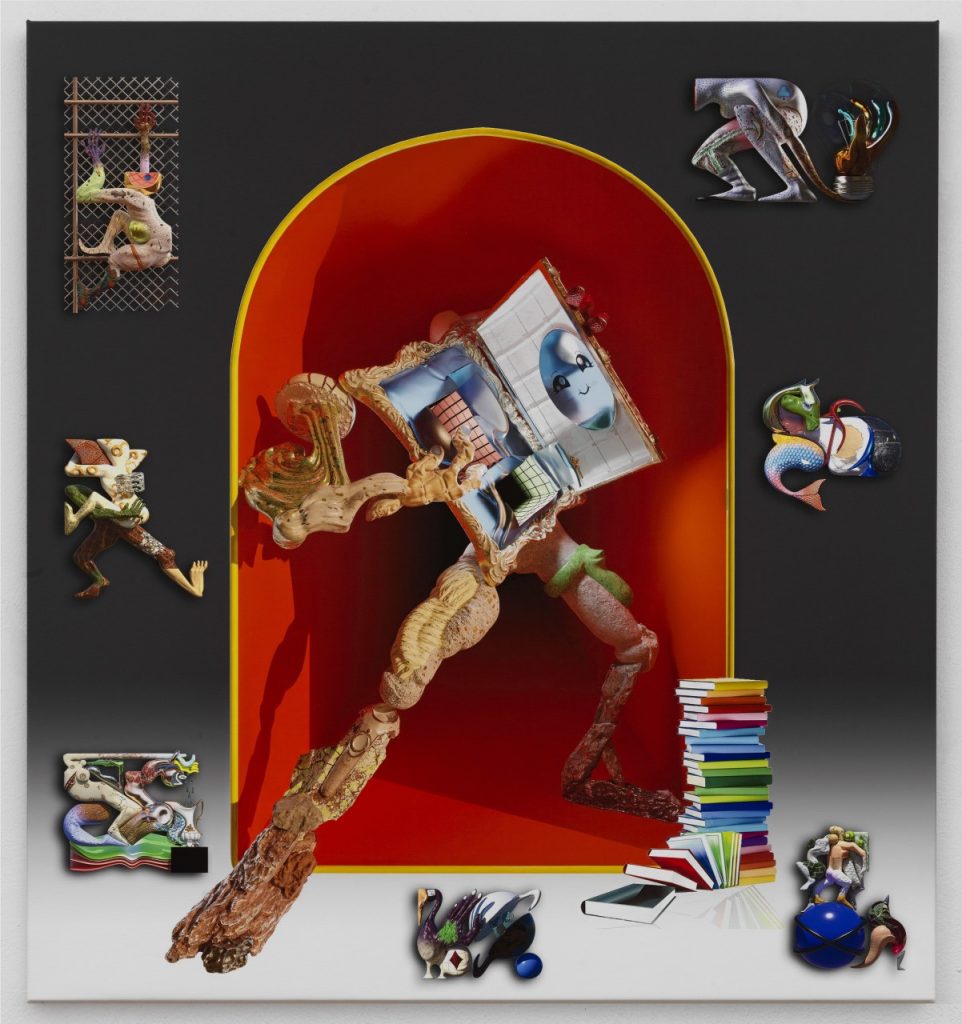

In his practice, the young French artist Kévin Bray explores the boundaries of various disciplines, such as video, (3D) photography, (digital) painting, computer graphics, animation, sculpture, graphic design and sound design. He then looks for ways to stretch these boundaries. The experiment plays a significant role in that. Bray then applies the implicit and explicit (visual) codes and rules of one medium to the other. How do they influence each other and how do they change the meaning of the artwork?

In his practice, Bray seems to refer in equal measure to art history, apocalyptic and dystopian stories and science fiction. He is also fascinated by fiction as a construct. When you watch a film, you often don’t realise how many factors have to come together perfectly to create a credible whole: from sound and art direction to visual language, camera work and special effects. Bray hopes to alert us to the fictional and deconstructed components in his work. He makes us aware of the underlying materials, manipulations and technologies that he has used to arrive at the end result. He mixes eerie and surrealistic elements and plays with the boundaries of the analog and the virtual. This creates a certain discomfort for the viewer, which makes for an exciting viewing experience. He uses both traditional techniques — including trompe l’oeil special effects from the world of cinema — as well as the most recent technologies.

Bray: “In my work I try to be a generalist of technologies, tools, and media. I believe that they are a language or at least an extension of it. I try to observe and learn from as many tools deriving from a diversity of systems, ranging from paintings, sculpting, writing, 3D modeling, filming, animating, composing, drawing methodologies and design to storytelling music making and sound design. Of course, I don’t master any of them but I try to understand and bridge all of those forms of language in unexpected ways, in order to encompass new realities and new perspectives on the shapes our narratives (social and political beliefs) are taking.”

His most recent works in “The Collective Shadow” consist of a series of sculptures, paintings and video projections that interact through different narrative techniques, to form a layered and hybrid multimedia installation.

Bray trained as a graphic designer at L’Ésaab in France, followed by a period at the design department of the Sandberg Institute and a residency at the prestigious Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam. He has exhibited his work at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, Foam Amsterdam, het HEM, the Dordrechts Museum and the K Museum of Contemporary Art in Seoul, among others. Bray made commissioned work for institutions including Kunstinstituut Melly and the Nieuwe Instituut.

During Art Rotterdam, the work of Kévin Bray will be on show in the booth of Upstream Gallery in the Main Section.

By Flor Linckens

We asked Rotterdam-based art professionals and collectors for their special tips. Enjoy your stay during Art Rotterdam like a local!

My favourite place to dine in Rotterdam:

Hard to choose, but at this particular moment: Tensai Ramen.

Where I would take a guest visiting Rotterdam to have a drink in Rotterdam:

I’d take them to Williams Canteen of course. For cocktails, that is. Kaapse Maria for beer.

My favourite art space:

Well, beyond Kunstinstituut Melly I’m going to say Daily Practice in Rotterdam West.

My outdoor sculpture in Rotterdam:

The Franz West “Qwertz” that I walk past each day.

My secret spot that makes Rotterdam special:

I can’t give the top secret spot away, but here’s the runner-up: Evermore

My favorite place to dine in Rotterdam:

La Pizza centrum or Louise petit restaurant

Where I would take a guest visiting Rotterdam to have a drink in Rotterdam:

Wine bar Le Nord or L’Ouest.

My favourite art space:

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, but since it’s closed its Depot is the second best.

My favorite outdoor sculpture in Rotterdam:

Le Tamanoir by Alexander Calder (corner of the ‘Aveling’ and the ‘Venkelweg’, Hoogvliet)

My secret spot that makes Rotterdam special:

It’s not that secret, but to me the most beautiful spot in Rotterdam; just stroll through the Euromast parc, grab a coffee at Parqiet and walk towards the Erasmus bridge and de Veerhaven.

My favorite place to dine in Rotterdam:

Rotterdam is teeming with great places to dine. There’s a restaurant for every mood and time, however I always tend to end up in the same places:

La Pizza (vongole, vongole, vongole), Tai Wu (so much fun to order by number), Vislokaal Kaap (always willing to make you a dish that’s not on the menu)

Where I would take a guest visiting Rotterdam to have a drink in Rotterdam:

My current fave hangout is Amore Rotterdam, especially when it comes to drinking their caipirinhas; However: it is mandatory to visit Café de Schouw in the Witte de Withstraat this year. This bar is Rotterdam’s one and only Artist Bar, where sooo many artists met and made new plans over the decades. De Schouw is closing this summer, so let’s party one more time, and make new memories that will end up in future books/blogs/films about the vibrant Rotterdam art scene.

My favourite art space:

Brutus Rotterdam is an unconventional space for art and more, housed in a massive old warehouse in the rough harbour area of Rotterdam. Artist Atelier van Lieshout has created a 10,000-square-foot paradise of artistic curiosity and exhibition to show exciting established artists, up-and-coming talent, embracing all artistic disciplines.

My favorite outdoor sculpture in Rotterdam:

On Heemraadssingel, well respected artist Maria Roosen was commissioned to create a monument for writer and poet Anna Blaman (1905-1960). This free spirited writer wrote openly about her lesbian relationships. Blaman was a prominent writer of great significance for the LGTBQ+ community in the Netherlands. In her time, she was a striking figure, a woman riding a huge motorcycle, which was quite uncommon. Maria Roosen chose this motorcycle to remember Anna Blaman by, appealing to notions of independence, freedom, adventurousness.

My secret spot that makes Rotterdam special:

The historic garden Schoonoord is a true Secret Garden in the very center of Rotterdam. I often take a break from the urban hustle and bustle in this beautiful time capsule of an early 19th-century private garden. The English Style garden stayed in private hands until 1973 when the family decided to open it to the public. A bridge was built and the old manor gate was put on the bridge. This made the park hard to spot as a public place and it still is to this day only known by the locals. There are over 1000 plant species at the garden and it became a national monument in 2000. Schoonoord is open daily from 8.30-16.30. (Please be mindful of the environment)

In the New Art section, LangArt is showing a new series by Maaike Fransen entitled How to Make a Living. The work comprises videos, but that does not do Fransen’s work justice. She personally designed and made absolutely everything in and for the six films, which she describes as parallel realities, one-person worlds – from the clothing and sculptures to the objects you see in the films to the performance.

Maaike Fransen (1987) graduated from the Design Academy in Eindhoven and earned a Master’s degree from the Sandberg Institute. Fransen is a multidisciplinary artist who dreams with her hands. Her work balances along the interface between fashion, design, performance and film. Using found materials as her starting point, she creates hybrid objects that balance between tools and autonomous sculptures and are often based on the human body.

What will you be showing at Art Rotterdam?

I am presenting a series of six films entitled How to Make a Living, including some of the two- and three-dimensional works from those films and a live performance in space.

In the series of films, different ideas and disciplines come together in what you might describe as absurdist-surrealistic one-person worlds. By ‘world’ I do not mean something big or wide, but rather a highly concentrated version of it. Perhaps habitat is a better word, or ‘comfort zone’, which was actually the working title of the series. They are essentially scenes of a unique, mutually related and interacting whole consisting of an installation, objects, person and action.

As a spectator, every film or performance gives you a glimpse of an alternative, parallel reality in which a mysterious ritual or unusual transformation takes place. I do everything myself and am a central part of the work, though I also try to disappear into it. You might also view the films as a series of moving self-portraits, DIY self-portraits.

You express yourself in videos, installations, performance and through fashion. It doesn’t get any more multidisciplinary than that. Is there a common theme in the work you produce in the various media?

When I consider my work of the past ten years, the common theme is perhaps that it is not so much one main theme, but a blend. Choosing has never been my strong suit. I always try to bring (too) much together. I have become skilled at collecting and collecting: combining, assembling, fusing existing objects and materials from my imagination. Creating unexpected interfaces and connections between very different, seemingly incompatible things. Intuitively and impulsively visually associating and constructing narratives. Perhaps I’m always striving for something like synergy or magic (1+1=3). Both I do this by allowing different ideas, forms, materials and techniques to work together, and in different disciplines and media.

Making things on and around (often my own) body is also a recurring theme in my work, as is trying to solve or work with personal topics, motives or problems. I like to erase the thin line between (my) life and (my) work by making things that are in between the real and unreal, between the normal and bizarre, the possible and impossible, things that slightly bend or question the status quo.

How do you choose a medium?

I consider the framework of the work: the question or assignment from which the need or desire to make the work arises, the resources at my disposal, the context or location where the work will end up or be presented. In short, the medium is often not preconceived, but a convergence of conditions.

As long as I don’t yet have a strong preference for any specific medium, I want the choice to develop during the process and feel like the most logical, natural or the most convenient and relevant one at that time. Making ‘something’ completely from scratch – even if the medium is fixed – does not fit my passion for collecting and compiling. I find it reassuring that I always have a find or a starting point somewhere in my studio that I can take in all kinds of directions, both imaginatively and materially.

What role does the result, i.e. the films, play in your work? Is this the primary focus or is the process more important to you?

I don’t consider the films that make up How to Make a Living as the result. They are certainly a result, but the installations, objects, sculptures and performance in the films stand on their own. As works of art and performances, I consider them a result. But because these films would be nothing without the things I made, and vice versa, I think the emphasis in this work is perhaps a little more on the things than on the films. And by things I mean the process, because I’m someone who comes up with an idea while working on something, and vice versa.

The work grows and evolves and slowly falls into place, or next to it. Sometimes, even after something seems finished, I continue to elaborate on it for a long time. It also happens that a work suddenly gain a new destination after being forgotten for a while. In a way, the films are an intermediate position, a snapshot. Making films or photographs helps me distance myself from the work for a while and truly see it, and then possibly finish it further. Filming is also a process in itself.

How to Make a Living consists of six short films in which the main characters have their own habitat with their own objects and rituals. Can you explain the idea behind this series?

In a literal sense, Making a Living refers to making or shaping ‘a life’, while figuratively it refers to ‘making ends meet’, supporting yourself financially. Ideally, you succeed at both and these two things smoothly coincide or emerge from each other, but in reality, at least in mine, they rub and clash and I am often confused and searching.

So, in this series, I try to do it for myself, partly fictionally and speculatively. ‘Make a life’ and at the same time reflect on it, fantasise about it. In some sense, these are sketches, a series of different attempts, a kind of exploration of alternatives and possibilities, as I place myself in different self-made settings. Which you could also view as abstracted jobs, functions or roles. Each work in the series tends to be subservient, useful, or at least entertaining, in order to earn its right to exist.

Would you consider the films an attempt to question your role as an artist in this world?

Yes, in a way I am attempting to intersect the arts with the everyday or necessary, with life and survival. In the films, I express personal wishes, dreams, desires, experiences, struggles, fears, disappointments, doubts and questions, such as: How do you live and survive in a capitalist system in which excessive value is placed on work, money and belongings? What is my place as an artist in this world? How do I keep myself alive from creativity alone, without commerce? How worth pursuing and how sustainable are individualism and self-reliance? How do you deal with alienation or loneliness? While making the series, I was recovering from a concussion. The enforced stagnation, uncertainty, worry, fatigue and limitations combined with bouts of hope and resilience from that time certainly influenced these dystopian and utopian worlds.

In that period of overstimulation and fatigue, I longed for a place of invisibility that defined peace and order, a place without all kinds of stressful and unnecessary things, where I could organise and execute things in my own way and where nothing was too much or too little. An equilibrium as it were. Yet the films are also disguised doomsday scenarios, or exit strategies. I was terrified that it would never go away and that I would become incapacitated for work with my faltering brain, that I would fall out of life and be unable to do anything. In the series, I take stock of and translate those things I was still able to do.

Apart from this personal layer, there is also a more general layer to the series: we are all born into a world that has already largely been imagined and created. How do you carve out your own place in it? What role can you play as an individual and to what extent do you have the freedom to shape that role and your own world? How can you use art and creativity for this? And how can you make a living from that without putting your work at the service of mass production and mass consumption.

From the very start of your career, for example in an early work like I-hat (2010), the tone of your work has been absurdist, playful and light. How did this become your preference?

Maybe that playful, light tone developed within me because of a lack of it as a way to deal with tension, heaviness and negativity. Creativity and absurdism as an outlet and escape, or as a way to put things that are difficult or annoying into perspective and sublimate them. Humour loosens up whatever is stuck in your mind and body.

You might say I have also experienced playfulness or play as a universal language that everyone speaks, knows and validates and with which you can easily connect with another person. To be honest, I have never consciously wondered if and why this is my preference. It is not on purpose or with much effort that I often create in this way; it usually just happens naturally. I think it’s my nature, a condition that suits me and makes me happy.

Geschreven door Wouter van den Eijkel

Kristof De Clercq Gallery is exhibiting new work by Ghent painter Veerle Beckers at Art Rotterdam. Her work is figurative and as a viewer, you immediately recognise Becker’s subjects, yet will never encounter them in the same way. Beckers navigates along the border between figuration and abstraction.

“For me, painting is very much about finding the right balance. It is a different translation exercise every time.”

Do you know which works you will be showing at Art Rotterdam? Recent work will be on display, paintings that I painted during 2022. The final selection has yet to be made in coordination with my gallery.

Do you take that work in a new direction or build on existing principles?

Every canvas I paint is separate from the previous one, separate from the whole. This is how I work. I don’t make series of works. My work evolves along with me as a person. In my life lately, for instance, apart from working in the studio, I’ve been trying to let go of my urge for control a bit more, and this of course influences my approach to painting. At times when I am more introspective, what I paint is more layered anyway, more loaded.

I noticed that your workplace is described in every article I read about your work. The path through your house to the attic with the countless clippings. This is rarely done as a rule, but it always happens with you. That cannot be coincidence. Can you describe your studio and its importance to your work?

People find it fascinating here. I should probably move, so that the focus will be on my paintings. 🙂 I paint in the house where I live. Working and living flow into each other. It’s an old house, narrow and tall. My studio is located in the attic, while the basement is where I live, cook, eat and have visitors. The walls of the hallway with the steep staircase that runs from bottom to top are covered with prints, photos, reproductions of paintings, post-its, collectibles…. You might say it is like a cabinet full of reference images, stimuli that nourish and inspire. But above all, they are stories, memories, twists and turns that provide clarity, a sort of anchor or backbone. I am extremely visual by nature and create stories with images. My studio is much more peaceful. There are fewer things hanging on the walls. Yet even there I feel the need to overload myself with images. Artbooks play a big role in my studio. I find open books inspiring.

I believe that the process of cutting and pasting and puzzling in my stairwell has to do with a fear of loss. A fear of forgetting, a fear of never feeling a certain feeling again, but above all, a fear of losing myself. The clippings and collages in the stairwell help me give my restlessness a place to land and are an instrument for understanding and exploring the world (my world).

I understand that you are able paint in any style, but chose this specific style. Is that a conscious decision or something that evolves intuitively?

Yes, it is something that evolves gradually. And it also helps to know yourself well as a person. You don’t enjoy doing something just because you can do it. I would not recommend that a person with ADHD paint like the Flemish Primitives. It’s about developing a way of working that makes you happy.

The way I paint also has a lot to do with what I’ve seen. As a child, I saw a lot of paintings. My father was an art dealer and sold work by Roger Raveel, Raoul De Keyser, Constant Permeke, Jean Brusselmans, Edgard Tytgat and others. I strongly believe that what you see and experience in your childhood is decisive for later in life, also as a painter in the studio.

Your work is figurative but in an abstract way. As a viewer, you immediately recognise the subjects, but will never encounter them like that in reality. You create just enough distance to observe the subject once again. Is that also what you’re after?

Yes, of course. For me, painting is very much about finding the right balance. I don’t just want to copy an image. Yet, I don’t want the initial image to disappear entirely. It is a different translation exercise every time. Sometimes I want to tell a story through colour, while other times, I try to convey an emotion through subject matter. Each image requires a specific approach. Of course, when I am painting, the original image fades into the background and I am only concerned with the canvas – with colour, composition and paint.

You are trained as a restorer of murals and paintings. In addition to your work as an artist, do you also work as a restorer?

No, though I worked as a house painter and decorator for a long time. I have taken several courses on painting and paint, and which also included restoration. But restoration has never really interested me. I realised very early on that I wanted to do something with paint and that I wanted to create. For a long time, I didn’t know which direction those painting courses would take me. All I knew was that I loved paint, colour and texture. Today, I notice that many things I have learned have come together in my studio and I enjoy that. The fact that I ended up restoring wall paintings had much more to do with my preference for frescoes and medieval wall paintings. I wanted to know how a fresco was made, how they used to create them and I wanted to be able to create them myself.

Written by Wouter van den Eijkel